by Roberta Holland, Journal Staff

Truth is, he’s both.

The folder contains a profile of one of Seven’s newest customers: a 56-year-old road rider who’s dissatisfied with his current, pedigreed Italian bicycle. He’s come to Vandermark hoping that Seven can work its magic and outfit him with two-wheel sublimity.

“There’s hand numbness and upper-back pain,” says Vandermark, 40, in a deep, measured voice. “Subjectively, I’d say make him a little more upright. a little more comfortable.” Then he chooses one of a dozen black binders resting on a bookshelf and flips it open to a document titled “Theory Behind Seven System for Determining Differential.”

“Now;” he adds, “how do we objectify this guy’s needs into math?”

Binders? Differential? Math? Exactly what kind of machine comes out of this place?

Vandermark and his 40-person company don’t build bicycles so much as craft precision instruments. Unlike most of the bikes manufactured by fabled boutique brands like Moots and Serotta, virtually every Seven is custom-built. Choosing among the company’s 30-plus road, mountain, cyclocross, and touring frames—nearly all of which come in high-end materials like titanium and carbon fiber—only kicks off a painstaking process. Two months after a customer orders his bike from an authorized Seven retailer, the finished product gets shipped from the company’s headquarters to the local shop, where wheels and components are installed. Average final price tag: $8,000.

“The people at Seven are perfectionists, and that’s not even a good enough word:’ says Ashley Korenblat, who worked with Vandermark at the high-end-bike maker Merlin and is now president of Western Spirit, a Moab, Utah-based bike-touring company. “Think obsessed, but with no negative connotations.”

Owners of Seven bikes, meanwhile, often sound like they’ve found God, and he’s apparently made of titanium. “After long rides, I used to have back problems. But with my Seven, it’s like I’m not even riding:’ says Brad Yoder a 45~year-old computer programmer and triathlete from Charlottesville, Virginia. “It’s as comfortable as a lounge chair.”

Vandermark’s preoccupation with building custom bikes began in the early 1990s. As an amateur racer and formal)y trained sculptor, he believed there was potential in providing discriminating cyclists with a tailored bike that was also a piece of art. “I realized that it was easy to design a bike that was really neat and rode well.”

Vandermark told me. “But could I really make one?” Vandermark didn’t want to live the life of the typical frame-building artisan, who gets sucked into the romance of fabricating elegant machinery and then suffers the hand-to-mouth reality of being a one-man show. So he obsessed over production processes, reading books on how companies like Toyota streamlined their manufacturing. In 1997, when Vandermark launched his company—which was named for the lucky number seven—he codified fit and construction methods that employees could learn. While many boutique frame builders will notch measly double-digit production runs, Vandermark’s $5 million company expects to produce 2,700 custom frames this year.

The odyssey of buying a Seven starts by plunging into a 12-page order form. Among its 108 questions, the workbook asks for multiple body measurements, whether you’re a “gear masher” or a “spinner;’ and how you would rate your current bike’s “drivetrain rigidity.” Once the form is complete, a fit specialist conducts an extensive pre-production, fork-to-finish phone interview—a process applied to all customers, whether they’re from North America or Australia. The data is plugged into seven’s sizing database, which generates a spreadsheet that will correspond with a frame design. Then Vandermark steps in, making sure, for instance, that they’ve specified frame tubes appropriate for a five-foot-eight, 130-pound male triathlete, which could be very different from the tubes that go into a frame for a five-foot-eight,130-pound male touring cyclist. “Every detail has an effect.” says Vandermark. “If we designed a bike for a man and then realized it’s really for a woman? We’d have to start from scratch.”

The final touches complete, the order goes back to the customer for approval. A computer then turns the data into a frame blueprint, which is sent to the Seven folks responsible for converting the paper bike Into a lusty ride.

A sign next to a side-entrance door at Seven’s humble, 15,OOO-square-foot facility reads, R1NG IF YOU’VE GOT DONUTS. One morning, Seven marketing chief Jennifer Miller and I come armed. The sticky-sweet breakfast, which is a tradition for Seven’s 24-person manufacturing staff, commences.

“Ohhh, the good ones!” says a guy wearing smudged safety glasses, grabbing a dough-nut dusted with chocolate sprinkles.

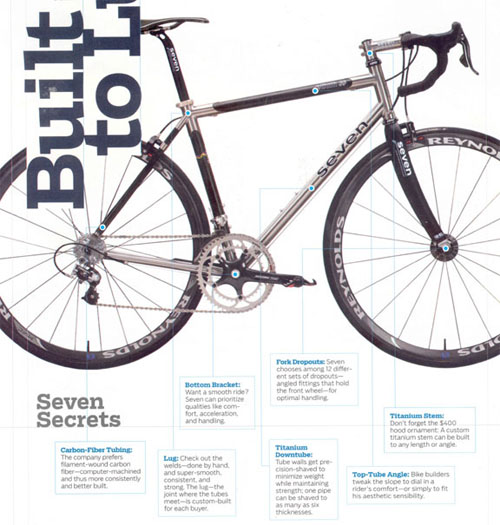

Amid the racket of metal being cut and welded, I’m led to one end of the shop, where a machinist starts the frame-building process by selecting tubing. Unlike other bike brands, Seven sources its titanium exclusively from U.S.-based mills, which have the highest fabrication standards in the world. A lot of Seven’s carbon-fiber tubing is “filament-wound”—another way of saying precision-made by computer-controlled machinery.

“There are no voids, and the compaction and ratio of epoxy to carbon from a tube six months ago and a tube today is identical,” Vandermark later explains, lapsing into geekspeak. “It’s predictable, repeatable, and durable.”

Instead of performing just one menial task, a technician in each of the company’s three manufacturing departments—machining, welding, and finishing—is responsible for seeing one frame all the way through to the next production stage. The machinist I’m watching, for example, must fabricate every tube for a Seven titanium frame. Farther down the line, I meet a welder named Skunk. He’s 37, shaggy-haired, heavily tattooed, and wears combat boots that are four sizes too big. But Skunk’s organized workspace reveals the methodical dweeb within. He even made the folding workbench that helps him better maneuver around his work.

A Seven welder can take four hours to assemble a single frame. You see the difference when you examine Skunk’s handiwork. “Look at that head tube!” he says while hovering over an Aerios road frame. “Welds like a stack of dimes!”

If the customer has ordered a Seven fork, it gets plugged with one of 12 different sets of dropouts, or aluminum fittings that hold the front wheel at a precise angle to the ground. Vandermark believes that changing out such bits can transform the way a bike handles.

Finally, the frame enters Seven’s finishing area. At one end, a burly guy with a ripped T-shirt furiously polishes a mountain-bike frame. Close by, a woman applies decals. And outside of two silvery paint booths is a rack holding frames with custom fade and “lucky-seven dice” paint jobs. Customers have also requested smiley faces, flames, multiple shades of green—you name it.

“One guy wanted a starry-night scheme with the moon,” a technician tells me. “On tubes. You have to rein them in!’

In the end, a Seven frame is finished only after it passes a 150-point inspection. “There’s a tiny bit of discoloration on the back of that cable stop,” says quality-control worker Tom Gawlick while poring over a Vacanza touring frame. “That’ll have to come out!”

You’d think Vandermark would be satisfied when the UPS man comes to pick up another batch of frames. But a perfectionist can never rest. His latest creation—the Diamas, a wildly tapered road frame that he claims is the world’s most customizable carbon-fiber bike—is running a year behind schedule, and orders are stacking up. When I ask Vandermark what’s causing the delay, he sheepishly confesses. “It’s me,” he says. “I’m the hurtle.”

Seven owners should only rejoice in such obsessive-compulsive pain.