by Justin Loretz

The most comfortable frame I’ve ever ridden and by default the most enjoyable too.

Quality like this doesn’t come cheap, though.

The Holy Grail, the Golden Fleece, the Ark of the Covenant, a basic understanding of the workings of the female mind – man’s search for each of these things is as fruitless as it is eternal. But one item, which until recently was on that very same list, has been found, at least according to What Mountain Bike’s Justin Loretz. He reckons his custom Seven Sola 29er is the most comfortable lightweight hardtail in the world. Here’s why…

The frame

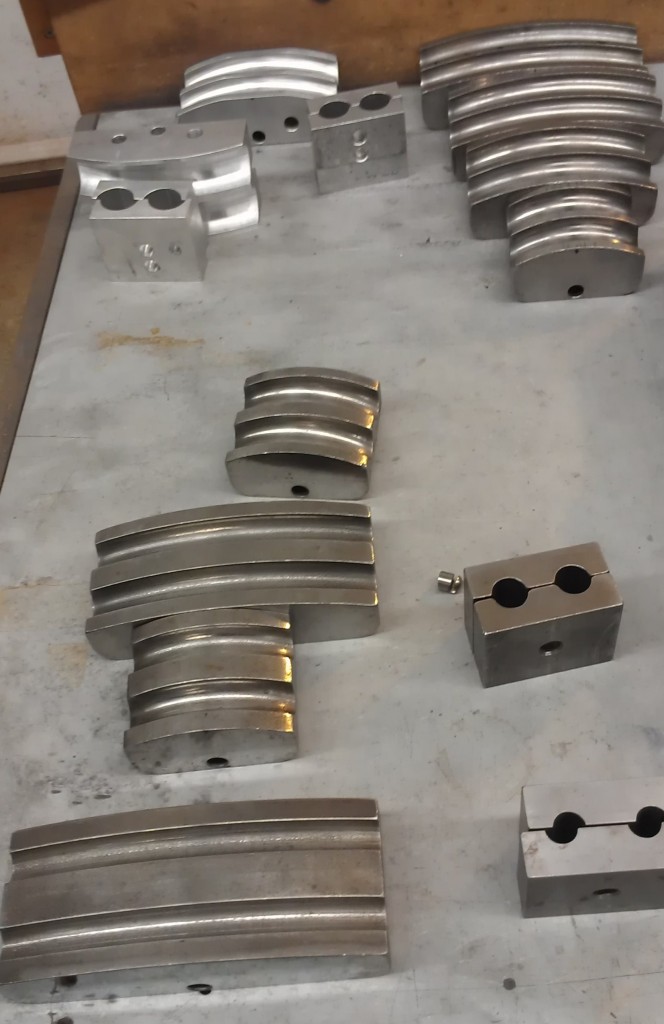

My Sola 29 SLX was born in Watertown, Massachusetts, USA, in a small but perfectly formed workshop in Walnut Street. It’s the place where Seven Cycles reside and perform some pretty clever frame building magic.

When you order a custom frame, you need to know what you want. I love riding hardtails and I knew I wanted a lightweight frame designed for 29in wheels. However, I didn’t want a steep angled, ‘built to ride like a 26er’ bike or one that would jack-hammer my fragile spine to pulp (I’m 40 years old and have two blown/fused vertebrae in my lower back).

Why a 29er? I’ve raced and ridden 29ers side-by-side with scores of 26in wheeled bikes and hands down, a 29er goes uphill faster. I believe it’s down to the way torque is delivered to the rear contact patch, with the larger wheels smoothing out spikes in your power delivery and providing enhanced traction. As a result, you can get away with using a lighter and faster rolling ‘summer spec’ rear tyre all year round. For a cross-country speed demon, this is a win-win situation. Of course, if you’re convinced you want 26in wheels, Seven can do that too.

With help from the guys at Seven I quickly settled on the Sola 29 SLX as being the right base model for me. Light and lithe are the page tabs it’s filed under – perfect for my spinning, accurate and mildly aggressive riding style, but not so good for stiffness obsessed heavyweights. To nail the geometry I measured up a few bikes that I’d ridden and liked for different reasons, namely a Scott Scale 29er and Niner Air 9 Carbon, to boil down my measurements. The geometry had to deliver a ride that was both fast and stable. It had to be able to confidently chase full- suspension bikes down hills and through testing singletrack, and happily drift on loose fireroads.

In the end, I went for a 71.5° seat angle and 68.5° head angle – slack compared to the current trend for 29er front ends that are as steep as those on road bikes, but I prefer to give steering input from the saddle rather than having ‘shopping trolley’ steering at the handlebar. With the guys from Seven I double, triple and quadruple checked everything – never a bad thing to do before the ‘go’ button is pressed, especially on a frame as expensive as this. Undoing welds is nigh-on impossible, so it’s worth getting it right.

With the design nailed all I had to do was wait. And hope. And dream. And then wait a little longer. One thing is for sure – buying custom isn’t for the impatient. Bespoke ‘one bike at a time’ builders like Seven will take the time it requires to do their jobs and that could be a month or it could be three. However long it takes, they’ll keep you informed along the way. Eventually the Seven Cycles box will arrive on the back of the UPS truck and I defy anyone not to have an elevated heart rate and sweaty palms as they pop it open.

As soon as I laid eyes on the raw, unbuilt frame I knew I’d been sent exactly what I’d asked for. The only question that remained was whether its geometry was going to ride the way I predicted it would. I built it up with a 100mm-travel RockShox SID XX fork and SRAM X0/XX bits. Wheels are either Fulcrum XL29s, Bontrager RXL29s or ENVE Carbons depending on the ride/mood I’m in, and finishing kit is a work in progress, with Control Tech Ti Mania and Easton parts popping up, as well as an AX Lightness Daedalus seatpost.

Suffice to say the bike as built is sexy, surgical and sleek. The natural silver-grey sheen of titanium is extremely attractive. When it’s washed it’s like a surgeon’s blade, when it’s dirty it looks like it was made for mud. Dirt just makes it look more handsome – a bit like the rider!

The ride

The ride, the ride… Oh if only I could plug you into my central nervous system. You’d see why I get home late, leave for work early and have an idiotic grin on my chops the entire day. Seven use their lightest Cirrus MTB titanium tubing on the SLX and the way it transmits vibration from the ground to your brain is like nothing else I’ve ever ridden, and I’ve ridden a lot of bikes in 20 years of testing. I was stunned to silence in 20 yards – that’s a new record for me.

The Seven has continued to leave me stunned in the three months and 800 miles we’ve been together. I’ve a mental Rolodex of how hundred of bikes have performed over my standard singletrack test loop. On the Seven, it takes a physical effort to wipe the smile off my face. I’m able to glide over terrain that normally makes hardtails feel hard and harsh, and in the big ring, spinning up what are normally horrible drag climbs I’m able to remain seated instead of resorting to the saddle-hover needed on most other hardtails.

As you turn the pedals you get the standard titanium frame feeling of having half-flat tyres, which takes a bit of getting used to. But there’s more. Seven have created a hardtail frame that feels more like a full-suspension one. When you hit bumps, the frame only transmits what feels like half the impact. It’s not just the rear end that soaks up the hits, either – the front end feels like it stretches a fraction and the whole chassis feels moulded to the ground.

Asked by other riders what the Seven feels like to ride I’ve found myself using terms like alive, dynamic, forgiving, even smooth and plush – two words normally reserved for full-suspension bikes. It doesn’t hurt that it weighs 21lb – a great weight for a 29er, which enables big ring, full gas riding whenever you feel like laying it down. On group rides my buddies now know that if I show up on the Seven they’re in for hurt.

In fact, the only one who’s not getting hurt is me. The comfort of the thin titanium tubes means I can indulge in rides where the time spent riding is the time I have available, not the time I can physically endure. I think comfort as a target for bike manufacturers has long been overlooked. Sure it isn’t as sexy a sell as ‘the stiffest’ but if you can’t bear to sit on the thing after a few hours, what’s the point? Over the course of a long ride it can add up to leave you fresher and more able to belt out the watts when other riders are beaten.

The trade-off is in chassis stiffness. To make a titanium frame that’ll build into a 20lb bike with a focus on comfort, you have to be prepared to give away something. Some would undoubtedly find this specific Sola SLX too soft, but for me it’s as stiff as it needs to be. Hammering it, it doesn’t ghost shift, there’s no brake rub and the frame doesn’t feel mushy. I’d say it’s 95 percent accurate at cross-country speeds.

That percentage would be higher if it had a tapered-steerer-compatible head tube and oversize bottom bracket (since delivery, Seven have begun offering BB30 as an option). But if it had those things, other details like the size and thickness of the main tubes would have to be adjusted and it would be heavier and maybe not as comfortable, getting away from the core reason for doing it this way. Besides, would I really notice the five percent increase in accuracy? Look at it this way: the Sola isn’t anyway near as stiff as my 2011 Niner Air 9 Carbon but it’s three, maybe four times as comfortable. Perfect for me.

I simply haven’t ridden a better bike for my kind of wide ranging cross-country/trail riding than the Seven Sola 29 SLX. A custom frame like this doesn’t come cheap and the top-end build pictured here would cost in excess of £6,000 – enough to buy two or three full-suspension trail bikes. But you can’t judge a bike like the Seven like that. It’s what one of my riding buddies described as the “wife bike” – the one you want to settle down with.