Press

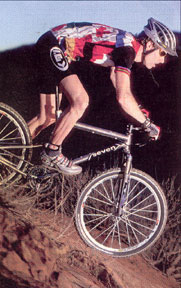

Champagne On The Trails: The refined flavor of the Seven Duo

Mountain Bike Action, April 2003

Don't expect to find a Seven at a bicycle shop near you. Seven don't play dat game. There are no production facilities at their Watertown, Massachusetts, headquarters, and we'll bet founder Rob Vandermark has never set foot in Taiwan. Seven makes their bicycles one frame at Ii time, and the majority of their bikes are made to an individual rider's specifications.

We've never ridden a hardtail Seven we didn't love (our last fling was with the Seven Sola in our April 2001 issue), but we had never ridden a Seven dual-suspension bike. Could Seven continue their MBA winning streak with the Duo'! There was only one way to find out.

Pouring the Duo

We could have asked Seven to build us a Duo based on one of the MBA wrecking crew member's dimensions. Since test bikes are returned after our thrashing, however (sometimes happily, sometimes begrudgingly), we thought it would be better to have Seven build a bicycle that they could later use for demo rides. So, our Duo arrived built for a rider of average height, weight and intelligence.

The Duo cuts a profile similar to Seven's diamond-framed hardtails, with two glaring exceptions: a seat tube set at an impossibly slack angle, and a vertical telescopic strut (we'll explain why it is not a shock in a second) from the swingarm to the seat tube. The frame is constructed of domestically sourced 3A1-2.5V titanium tubing.

Seven slapped on the type of parts you'd expect to find bolted to a $3195 frame: Shimano's 2003XTR components (including XTR disc brakes), a Fox Float 100RLC fork, Mavic CrossMax tubeless-tire wheel set, Thomson seatpost, Selle Italia Flite saddle and Hutchinson Scorpion tubeless tires.

Shock Vs. Struts

Fox Racing Shox makes the Duo's shock, which is bolted in two places to form the forward member of its triangulated swingarm. Because the shock is integrated into the rear frame, it is called a strut. Inside the Fox strut is a conventional hydraulic damper and coil spring arrangement. There is an external rebound clicker on the left side with six positions. A Schrader air valve on the shock eliminates the need to replace or preload the coil spring to accommodate heavier riders or different riding styles. The air "helper" spring is an intelligent way to fine tune the strut.

The heart of the Duo's rear suspension is called the Mono-Link. This hollow piece of magnesium houses the bottom bracket and connects the front section of the frame to the lower end of the swingarm. The Mono-Link acts like an upside-down swing link. The casting pivots on sealed ball bearings and incorporates a mount for Shimano's E-type front derailleur and an integrated cable guide.

Popping the Cork

In the saddle: It is fortunate that the majority of Sevens are custom made, because the Duo's super slack seat tube just wouldn't work on. a three-sizes-fit-all production mountain bike. Why? The fore-to-aft saddle position changes radically when setting the saddle height. Raising the saddle from a seat height of 29 inches (measured from the center of the bottom bracket to the top of the seat} to 30 inches moves the saddle rearward 3/4 of an inch. Riders with long legs and short torsos will find themselves too far behind the bottom bracket and forced to run a short stem. This potential problem can be eliminated (or at least reduced) by carefully planning the building of your Duo with Seven.On the trail: The Duo absorbs the vibrations created by a rough trail, and it does it at all speeds. You can thank a three-punch knockout combination of Seven's titanium, Hutchinson's tubeless tires and the Duo's suspension for this supple ride. The Duo rider floats in a neutral position; there is no weight favoritism to the front or rear. The rear suspension feels too soft in the parking lot, but once on the trail it starts to show its stuff.

In the turns: The Mono-Link and Fox fork work together like they are brothers, not competitors. Don't set the Fox fork to mimic the bob-free feel of the Mono-Link. The fork should be set on the active side (softer settings) rather than stiffer settings. This allows the front tire to bite in tight turns and on fire road descents. So what does that have to do with the Mono-Link? The tail end of the Duo follows the front wheel very precisely. Setting the front end too stiff will cause poor control in the turns, and this will be mimicked by the rear tire.

Climbing: The Duo climbs deceptively well. It doesn't feel fast, lively If or overly responsive (this is true while hammering on the flats too) when throwing down an effort, but don't be fooled�you are moving along. One crewer underwhelmed by the Duo's performance after a solo ride was instructed to go back out on the Duo with a group. He came back surprised after holding his own against normally faster riders.

Hammering: Part of your weight is uncoupled from the rear suspension when you rise out of the saddle for an attack, because the cranks are attached to the Mono-Link. This, and the fact that the rear suspension lengthens as it compresses over a bump, eliminates any tendency for the rear end to settle when you mash on the pedals.

Braking: This was our first extended test of Shimano's XTR hydraulic disc brakes, and they more than lived up to the expectations culled from a sneak peek of a pre-production version of the system (A Weekend On Shimano's New XTR Group", MBA November, 2002). The brakes require a short break-in period (one to two hours of trail riding) before you'll feel their full power. Once past the break-in period, these disc brakes feel like perfectly adjusted V-Brakes that never fade nor need adjustment.

The stopping power is unbelievably easy to modulate, unlike Shimano's on-off-switch power of old. These brakes will go further to improve trail access in America than any other recent mountain bike innovation. Why? Only the most ham-fisted beginner will lock these brakes. All other riders will take advantage of the beautiful modulation and power these stoppers offer and scrub speed without ripping up the trail. Finally, while we experienced brief periods of squealing while applying the brakes after a water crossing (the squealing disappears quickly), the brake pads never rubbed or dragged on the discs.

Going Flat

Our Duo started making a racket under hard efforts. The sound was similar to pedaling a bike with a loose bottom bracket that had been totally degreased. We found that the lower Mono-Link bearings had developed excessive play. This was easily corrected by tightening the bearing from the left side with a 15mm pedal wrench and an eight-millimeter Allen wrench. We mention this because the exact same problem occurred when we tested the Maverick ML-7 (which uses the same rear suspension design). A coincidence? Maybe. It is still a good reason for Mono-Link riders to watch this critical area.

We pointed out earlier that the slack seat tube creates challenges for finding just the right seat position. If you are adding a Duo to your stable, we strongly recommend that you have Seven custom make your bike based on your exact body dimensions. Of course, why would you buy a Seven if you weren't going the custom-made-frame route in the first place?

Toast of the Trail

The Duo is the consummate trailbike. Its relaxed geometry and four inches of mono-link suspension mean that you won't get that feeling of instant acceleration with every touch of the pedals. Instead, the Duo accelerates smoothly, its tires hook up on almost any surface, and you get an efficient transfer of power. You'll want to stick with Seven's hardtail offerings for pure cross- country racing, but for a trailbike that has few peers and will drop you off after an epic ride with power still in your legs, the 2003 Seven Duo is an excellent year.