Tag: Photos Of Note

Behind the Mask

Nestled snug in their box, the tubes that will become my frame roll, with the jig, from machining to welding, where they wait to be claimed. Who welds each frame is a matter of chance. Whichever welder is available at the moment takes the next frame in line. In my case, that welder is Stef Adams. Coincidentally, Stef welded my other Seven back in 2005, an Elium SL, and she did such a good job with that one that my thirst for a new bike was stifled for nearly a decade.

While in the machining stage, tubes get coated with grease, dust, shavings, “permanent”marker, finger prints, oil, and who knows what else. To ensure that her welds will last a lifetime, Stef cleans each tube in a two stage acetone bath which wipes away everything, including the boastful claims of the marker. By wearing fresh, cotton gloves she keeps her own finger prints off the tubes in the process.

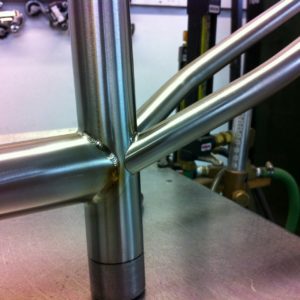

Sevens are TIG welded (the acronym stands for Tungsten Inert Gas). We pump argon through our frame jigs and into the tube sets as we weld them. The inert argon won’t react with the molten titanium, which is why we use it to “clean” the inside and outside of each area to be welded.

Stef assembles the clean tubes back into the jig, then hooks up a gasket to the head tube in order to create the back purge, plugging all of the external holes in the frame (e.g. where water bottles will be mounted) with stoppers. Internal breather holes, previously drilled into the tubes, will allow the gas to flow from one tube to the next until all of the tubes are overflowing with argon. Argon also flows out of the welder’s torch which protects the outside of the tubes.

A gauge at each welding station lets the welders know when there is enough argon in the frame to begin welding. Stef checks the gauge and begins tacking one tube to the next. A tack is a small spot weld that holds the tubes in place. They make freehand welding more manageable.

Out of the jig and onto the welding table the tacked frame goes. Stef works in a most graceful fashion, twirling the frame around the table, welding a little here, a little there, with the smooth, precise movements that she has perfected over the course of more than seven thousand frames.

Little by little, the frame gets closer to completion. Stef says it takes a few hours to weld a frame as “simple” as mine, but that couplers and other options can add to that. My frame is simple in that it is a straight forward mountain bike, with no additional features or options that need to be welded on. I clarify with her that it is also awesome, and she agrees.

Below are the bridges and zip tie guides. Not too many, means not too complicated.

Perfectly round, overlapping droplets of molten titanium bond the tubes together. A stack of dimes, fish scales, whatever you want to call them, they will hold the frame together for the rest of its life. I think they are beautiful. One of the many artistic achievements of the welder is to make it appear that the weld was done all at once, one droplet after the next, until the entire tube is welded, but in reality, they work in tiny centimeter long increments, which is why the frame is flipped, spun, and maneuvered into different positions as they go.

For a novice, welding can be pretty scary. There is electricity, intense heat, and a light so bright it could blind you. Behind a camera lens, it looks like a brilliant purple and blue light.

But from behind the welder’s mask, it’s actually quite pleasing. The welding mask is tinted so dark that, to Stef, it feels like welding by candle light. She works slowly but steadily. Aiming the torch with her right hand, she increases the heat until it’s so hot that the spindly titanium bead in her left hand melts when she dabs it on the tube. Each droplet adds material and strength to the weld. This style of welding bikes is called the Puddle Bead Method, and was pioneered by another welder at Seven, Tim Delaney. Stef is a master, and does a great job of explaining what she is doing while she works. She makes it look so easy, but I know that if I were at the helm, there would be shouting, catastrophe, and probably a fire.

A job well done and a small token of appreciation.

The next time I check on it, the frame is all together and hanging up in the final machining department, ready for the next steps, so close to completion.

After the Flood

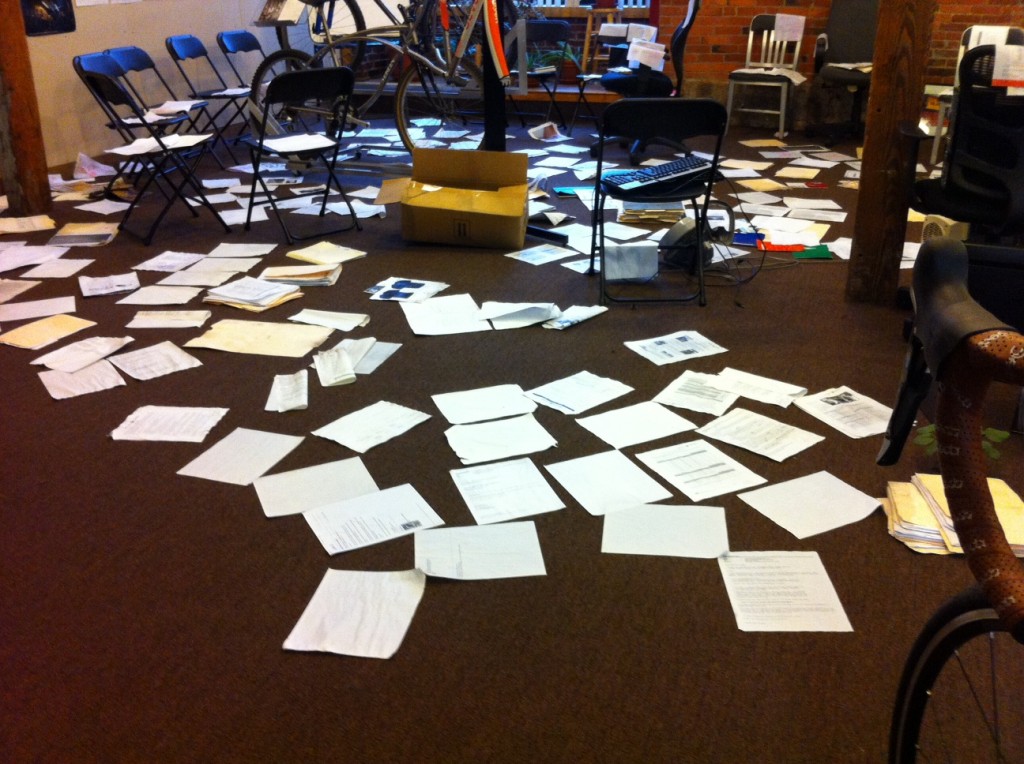

It’s funny to be writing about a flood after we’ve just written about a major snow storm, but the two are not wholly unrelated. The weekend after the storm, temperatures plummeted here, as they did in most of the country, and the heat in the vacant space above our office stopped working. Pipes froze, burst, and then unfroze, which lead to a prolonged rain shower down here where we work.

So, we sustained some damage. The better part of this week thus far has been dedicated to figuring out which of our computers are salvageable and attempting to dry out our space.

The damage will be hard to quantify. We will replace equipment, and that will have a dollar value attached to it. The building management’s insurance will cover those things. For once, a flood/fire/alarm didn’t originate with us.

The bigger and less quantifiable harm will be in lost research, smudged notes and lost reference material. Living in modern times, we all marvel at how dependent we have become on technology, but an event like this one points out how dependent we still are on old-fashioned pen and paper. To borrow a phrase, for a custom frame builder, the pen may in fact be mightier than the torch.

The key, we understand, in these situations is to find the positive, and of course, there are many. First, we learned a lot about the elasticity of our systems. Bike production didn’t stop, just because the front office was incapacitated. Second, we were forced to rid ourselves of a lot of stuff we no longer needed. When you’ve got your head down, building bikes, dreaming up new products, trying to navigate the world as a small company, you seldom take the time to clean out the old. Now the old is out, and we have room for some new.

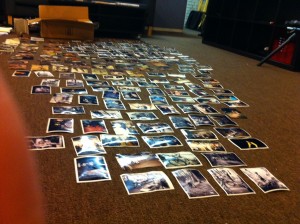

Finally, the flood did a great job of flushing cool, old stuff out of the corners, reference books that have influenced our thinking, old photos of the team when we were younger, and prototype parts, the constructive failures of past projects. All of it has us thinking differently.

Sometimes you don’t want to start over, but starting over is valuable nonetheless.

Photo Friday

An ongoing series of shots from the shop floor and beyond…

The waste container in the mix booth. Fifty shades of awesome.

Photo by Rob V.

Two Hour Loop

Normally I’d bail on an afternoon ride at the end of October if I knew I had to be back in time to shower and dress in order to make the three o’clock shuttle. That’s too much pressure. In Vermont, however, a few weeks past peak foliage is still a feast for the eyes. My girlfriend and I were in Burlington for a friend’s wedding, and brought bikes on the off chance we could squeeze in a leaf peeping jaunt prior to the festivities. Midday Saturday presented us with about two hours of down time, so we decided to take advantage even if we had to hurry.

We suited up and shoved off, traveling south towards Mt. Philo. A few miles out of town and the hills began to roll. Red and yellow may have been lacking but orange made up for their departure in grand form, blanketing everything that wasn’t Lake Champlain with the rusty colors of autumn. With each up we’d get a postcard worthy view, albeit brief, before careening back down. Over and over again. The higher we climbed, the better the view. By the time we reached the base of the mountain, it seemed like we could see the entire valley. We weren’t craving any more climbing, so when the park ranger explained that the road to the top was closed for a car race, we decided to ride around it instead. The extended loop meant I might not have time to iron my shirt, but I had a sweater I could wear over it, so we carried on. A few farms, hundreds of cows, and a covered bridge later, we were on the way back to the hotel.

A powerful tail wind helped our time crunch and had us back in just enough time to swap Lycra for dress clothes. I’m writing this down to serve as a lesson for me, and any of you who also opt to sit out short rides, because in just two hours we had a ride I’ll remember for a lifetime.