We are proud to say there were a lot of Sevens at Paris-Brest-Paris this year, and we had the chance to spend some time with one rider, Henry van den Broek, who is local to us and a Ride Studio Cafe regular, to hear about the adventure of riding 1200km.

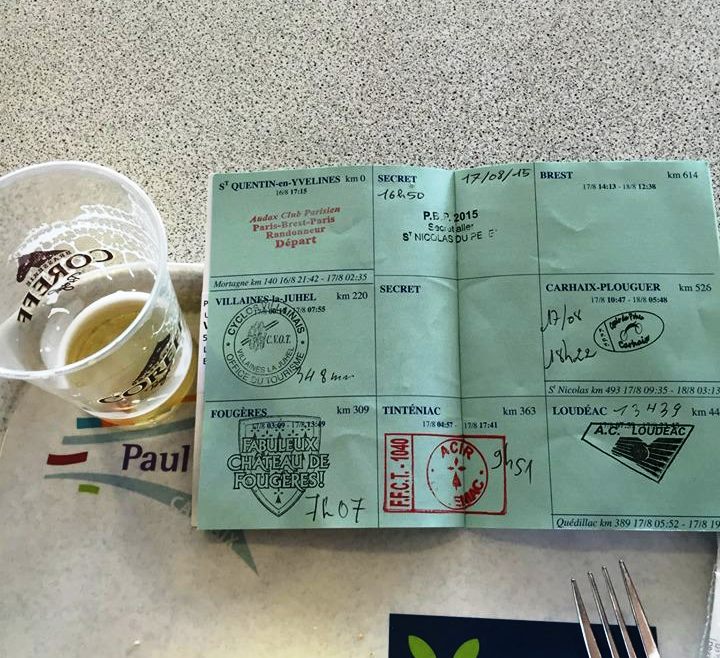

He says, “I started Sunday evening in the 90 hour wave at 18:30. Apart from some short stops at the controls (less than 30 min), I rode through the night and the following day for 24 hrs until Carhaix which is 525km, just before the halfway point in Brest. After sleeping for 3 hours on a field bed in a gym, I left that night at 11pm for Brest and kept riding through the night and next day until Fougeres (921km) where I arrived with fellow Seven rider Dave Bayley Tuesday night.”

He continues, “Dave I met in the morning just after the Loudeac stop. This had been a tough morning where I felt pretty groggy and had a hard time making speed, but after plenty of caffeine and ice cream I got my mojo back. Dave continued that night for Fougeres, while I slept on a gym mattress for 3 hours and left at 4am Wednesday for the last 300k to Paris, where I arrived at 8:30pm, finishing the ride within 74hrs.”

When you’re speaking to someone who aspires to riding for 3 days straight, the first question is always going to be, why? Henry laughs when we ask, “Why do I do it? On the ride, I sometimes wonder myself what I am doing, but I ride for the sense of adventure, exploring, seeing new places, new landscapes. Randonneuring reduces life to its basics. You are just eating, drinking. You ask, how is my body feeling? You become your own little world. Also you can meet friends through this shared suffering. On long rides, you have a chance to meet, hang out.”

Henry only started randonneuring three years ago, encouraged by Patria and the crew at Ride Studio Cafe, and then he wondered if could even do it. 200km? 300km? 600km? Now he finds himself wondering what’s next after PBP.

“With all the preparation I had,” he says, “I was not that worried. I did 1000km in July, and PBP is not that much more. During the ride, I got more and more confident. Unlike many of the brevets I did in the season where there are typically 20-100 participants, there were more than 5000 people starting at PBP, all trying to finish. This year less then 75% percent finished.”

He continues, “When things get hard, typically I do a check up. Hard can be multiple things, overheating, tiredness, pain, sleepiness. How are my back, my arms, my legs? Most things can be solved by eating. Electrolytes and sugar can cure most problems. Grogginess is a tough one. I had three hour sleep stops on Monday and Tuesday nights, but it wasn’t enough. The jet lag didn’t help either, flying into Paris two days before the event. Coffee was the only way to get over it. Chewing gum can help. Next time I want to try caffeine gum. You think it’s a mental thing, but that really comes back to sugar levels. Your brain is just saying it needs more fuel. This is about being in tune with your body.”

It is not every day you ride 1200km. Most who finish PBP only do it once in their lifetime, so strategizing for a ride like this comes down to the experience of the “shorter” brevets and reading about how others have handled the distance.

Henry says, “What I realize now is you have to be careful how much power you’re putting out. You have to measure your effort, not go too hard. Even 1% over your pace will catch up to you over these kinds of distances.”

Henry’s Seven Evergreen SL was built with more than just PBP in mind. This is a bike that Henry uses on group rides with the RSC club. He has done the full brevet series on it. And now that it’s fall, he’s racing cyclocross on it as well.

He says, “I love the frame. I love the versatility of it. I was always completely worn out by my old bike. This season I’m on the Seven on 38mm tires with supple casings. It’s so smooth. They roll so well. The Evergreen has a lot of clearance, so you have choices in tires. The disc brakes give you reliability in all weather. It’s very stable, too. I ride with a very light touch on the bars, so no back pain ever.”

“I also really love the custom paint,” he adds. “So many people look at my bike and love the paint job. It’s orange from Holland. I always get attention with it, and it’s really MY bike. It has my name on it, my color, made for my body. It’s a statement. It’s me. I feel very together with the bike.”