By Kate Harris

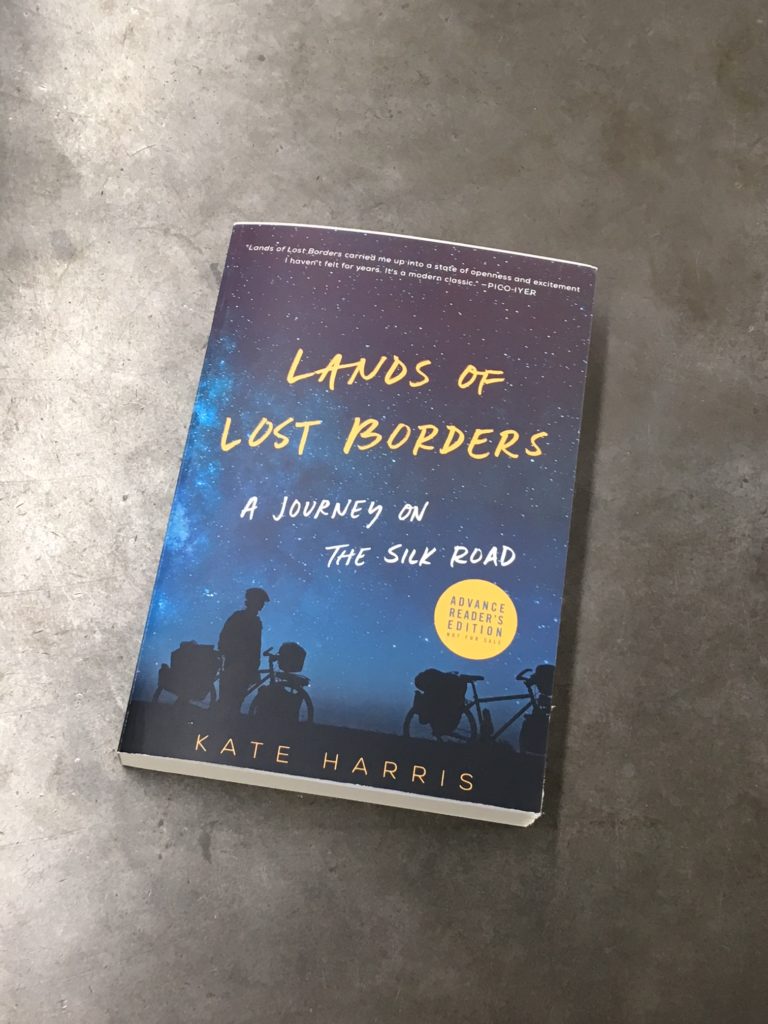

This is the third in a series of articles documenting Cycling Silk, A year-long research expedition across Asia.

In the world of strict plans and fixed agendas, detours are just distractions. But on the Cycling Silk expedition, detours often prove the destination – and not just because we frequently get lost. So when KuzeyDoga, an award-winning Turkish NGO, invited us to explore their biodiversity conservation projects in the borderlands of eastern Turkey – wooing us with wild animals, wide open spaces, and a visit to a Turkish bath – we knew it would be worth diverting from our intended route for a visit. After all, we hadn’t showered in a week.

So we steered south, away from the Black Sea, and began climbing onto the Kars Plateau, swapping heavy rain for heavier snow along the way. The roads grew so slick with ice we had to work twice as hard to go half as fast. Sometimes we couldn’t bike at all. Climbing a pass during a blizzard, the snow not so much falling as firing, flakes sharp and aimed as arrows, the police stopped us and made us cross the pass in a truck (driven by Osman and Mustafa, of course.) At least the heated cab offered respite from the snot-crackling, lung-stiffening cold. Surviving on the bike in such conditions required cartwheel breaks to centrifugally force blood back into extremities. While I exulted in this suddenly polar world, cryophile that I am, Mel may never join me on another winter adventure again, even if she someday thaws out from this one.

Whether because of the cold or despite it, we fell in love with Kars. The Plateau is a territory of enchantment: foxes loping across plains wide as thought, owls patient as stone on signposts, mountains giving cold shoulders to the world. A place more sky than earth, no wonder it set us soaring. We had good company up there: slow-reeling vultures, skinhead buzzards, fang-billed falcons, and many other birds populate Kars skies. Since we visited in the cold heart of winter, though, most vagrants of the air were off sunning themselves at the equator. Birds of prey migrate by skipping like stones from thermal to thermal, rising on one column of hot air and gliding down to the next forming, back and forth to Africa, Europe, and India, stopping in the South Caucasus along the way. If only bikes could be physically powered by the same principle.

While territory is an instinctive concept for birds, the political divides we map onto their habitats are meaningless to them. There’s no explaining borders to the birds; they fly far above our fences. But even so, fences define boundaries, however arbitrary, that can fragment the habitats where birds stop to breed and feed during migration. This is especially true of the borderlands where KuzeyDoga works, including the Aralik-Karasu marshes skirting the base of Mount Agri (aka Ararat), on the border of Turkey and Iran, with Armenia and Azerbaijan nearby.

Legend has it Noah’s Ark first struck dry land on Mount Agri/Ararat’s summit, and the rich biodiversity here seemed to fit the story of a bunch of creatures spilling out of a boat. Down off the Kars Plateau, the wetlands rarely freeze, an oasis of iceless water and grass in the cold South Caucasian winter. But as fertile land, the marshes risk of being drained for agricultural use in one or more of the countries involved. What one country does with its wedge of wetland impacts the rest, so keeping this ecosystem intact requires a cross-border approach. That’s no simple task for countries in protracted conflict, as they are in the South Caucasus.

But when politics is the barrier, transboundary conservation is possible, at least in some form, through transboundary communication: individuals and NGOs talking across contested borders, sharing data and ideas directly or indirectly, and where possible, harmonizing approaches to nature protection in each place. This helps protect biodiversity as much as possible in the short-term, given politics, and builds a robust case for more formal transboundary cooperation down the road, once political situations improve. So peace, however desirable, is not a prerequisite for conservation across borders – and good thing, because in many places, we can’t afford to wait.

If explaining borders to birds is an exercise in absurdity, imagine us trying to explain, using only hand gestures, to people who already think we’re nuts, exactly what it is we love about being cold and dirty on the back of a burdened bike for months on end. The answer, at least in part, is how transcendent a Turkish bath feels after a grimy stint on the road. Scrubbed clean down to different people, we thanked KuzeyDoga for a fantastic visit, and promised to return to the Kars Plateau someday – in summer. Then we hit the road to the Democratic Republic of Georgia.

The weather continued to be frightful, cold as bones, but we soon acquired a companion who warmed our hearts, if not the rest of us. At the top of the final pass, close to the border, a dog materialized out of cold mist, wagging her whole body and batting iced lashes at us. We patted her and offered her trail mix; it was that or raw oatmeal and pasta. She shunned our food, for good reason, but ate up our affection, and when we biked away, she galloped along behind. We named her Baklava, and welcomed her to the Cycling Silk team. Alas, just a few hours later, Baklava was dognapped by her so-claimed owners. Probably for the best, since smuggling her across the border would’ve been tricky, but such is the twinned happiness and heartbreak of this journey: making new friends, then moving on.

A few days later, on the far side of the Turkey-Georgia border, we reached the Caspian Sea sooner than expected. At least the puddles, swallowing the entire road and then some, made us feel suddenly at sea. So did the new language. Kartuli, the Georgian tongue, had us choking on consonants while pronouncing crucial words like gvbrdghvnit, which means “you tear us into pieces.” So that’s what wilderness has been saying to borders all this time! We couldn’t quite make it out until now. Fortunately for us, some people spoke English in Tbilisi, the capital city of Georgia, where we stopped for a few weeks to interview conservationists, scientists, and politicians about transboundary conservation in the South Caucasus. The WWF-Caucasus office generously let us camp out in their conference room during our stay in the city, and after sleeping on the cold ground for months, sleeping on a carpeted floor was the apogee of luxury.

But winter was waning by the time we hopped back on the bikes, destined for the Lagodekhi Protected Areas in the extreme northeast of Georgia. As we pedaled there, our legs and lungs bounced with all the spring in the air. After months of combating the cold, we could finally relax into the weather: it wasn’t going to filch a finger or toe from us when we weren’t looking. Snow still crowned the Greater Caucasus mountains, but the lower slopes were hackled in trees, trunks raised not in alarm but acclamation, branches shaking fists of buds in joy, or something like it.

The Lagodekhi Protected Areas, the oldest nature reserve in Georgia, is famous for its fairytale forests and ruins. We took a few days to explore Lagodekhi on foot, guided by Giorgi, a ranger at the reserves. On our hikes he wore a dapper shirt, vest, ranger jacket, hat, and rubber boots; we wore matching filthy outfits, carried far too many cameras and lenses and tripods, and staggered on legs more used to pushing pedals than supporting strides. But Giorgi was patient with us, if bemused by our compulsions to snap a photo every two steps and hug every second tree.

No wonder we looked suspicious to the Georgian border guards we met in the woods, on our way to Machi castle, ancient ruins on the Georgian-Azerbaijani border. But after checking our passports and establishing that we weren’t, contrary to appearances, completely mad – only partially and harmlessly – they relaxed and hiked along with us, happy for company on a lonely patrol. A few days later we showed our passports to some more border guards, then biked into the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Our first mission in Azerbaijan was to track down Zakatala, a Strictly Protected nature reserve running parallel to Georgia’s Lagodekhi.’ Track down’ turned out to be an apt expression: the paved road turned to calloused dirt, then a stream, then cobblestoned mud, then nothing but a river valley with forests and mountains beyond. No welcome signs, no fences, no interpretive center for visitors, as we found just across the border at Lagodekhi; just wilderness protected by its relative inaccessibility.

But locals still access the reserve illegally, according to people we spoke to, where they hunt, collect mushrooms, and chop firewood at the risk of huge fines. With few other means of income, they don’t have much of a choice, here or many other places in the South Caucasus. Everywhere we went, again and again, we saw how local people play such a crucial role in wilderness conservation, and how much environmental protection depends on sustainable development. Given the choice between going cold in the winter or chopping down a virgin beech for firewood, anyone in their right or left mind would take ax to trunk, no matter how much they love the forest. So if we don’t take care of people, the planet will suffer; if we don’t care of the planet, people will suffer. Both have to happen at once, and we’re all in this together. Whether we’re talking about birds or trees, you or I, here or there, we all inhabit the same spinning ark.

From migratory birds that breed in Mount Agri/Ararat’s meltwater to castle ruins growing forests in Lagodekhi, so many of the natural wonders we explored in the South Caucasus had a human, historical dimension as well. Riding the Silk Road through these places was intense schooling on the fact of flux: all the conquests and constructs of their storied pasts, all the countless people who lived and loved and grieved in their day, just as we do in ours, are nothing but legend and rubble now, nesting grounds for birds and fertilizer for forests.

Flux is the fact of wilderness conservation too, especially across the fickle and changing boundaries of politics. Conservation is not about preservation: it does not aim to keep nature static, fix forests in formaldehyde, establish isolated Protected Areas we can then walk away from, patting ourselves on the back for a job well and forever done. Instead, wilderness conservation is an act of perpetual vigilance and flexibility, a commitment to letting the natural world exist and evolve, across borders and through time, without an excess of human meddling. Because sweet air, clean water, rich soil – and by extension human health and happiness – depend on a biodiverse planet. Because every generation deserves the chance to cartwheel into cold wonder, get lost in a primeval forest, wake to birdsong raining on a tent. Because wilderness, like the Silk Road itself, is a place of instruction, with lessons to teach we can’t even begin to imagine.

Hiking around the Ani ruins in Kars, next to the Turkey-Armenia border, I swear I heard a door slam, somewhere deep underground. The noise said no road is long enough to learn everything I want to know, get everywhere I want to go. Not even the Silk Road, no matter how many detours we take. Genuine borders exist, biological and temporal, that none of us, however monied and powerful, can transcend. So maybe the best we can do, in this fleet and singular life, is follow the example of the birds, and seek out thermals: whatever makes us rise, tosses us aloft, sends us soaring.

I know a wood where each leaf is the distance between two dark towns, where each branch contains what is granted to kingdoms and I know the wind that carries all that away. -Don Domanski