Clocked Screws and Screw Slot Alignment

"Clocked" refers to the condition when screw head drives (slots or sockets) are in visual alignment with each other.

Once a year or so, a rider asks why we don't clock our head tube badge screws. A fair question if the rider is a woodworker. However, clocking is not a technique used in precision metalworking.

Some people misunderstand clocking as a mark of quality or attention to detail; it's not, in the context of metalworking. It is not a sign of excellent and proper work. At best, it's a sign of cost without value (or vanity sans understanding). At worst, it reduces the component's accuracy, durability, and safety.

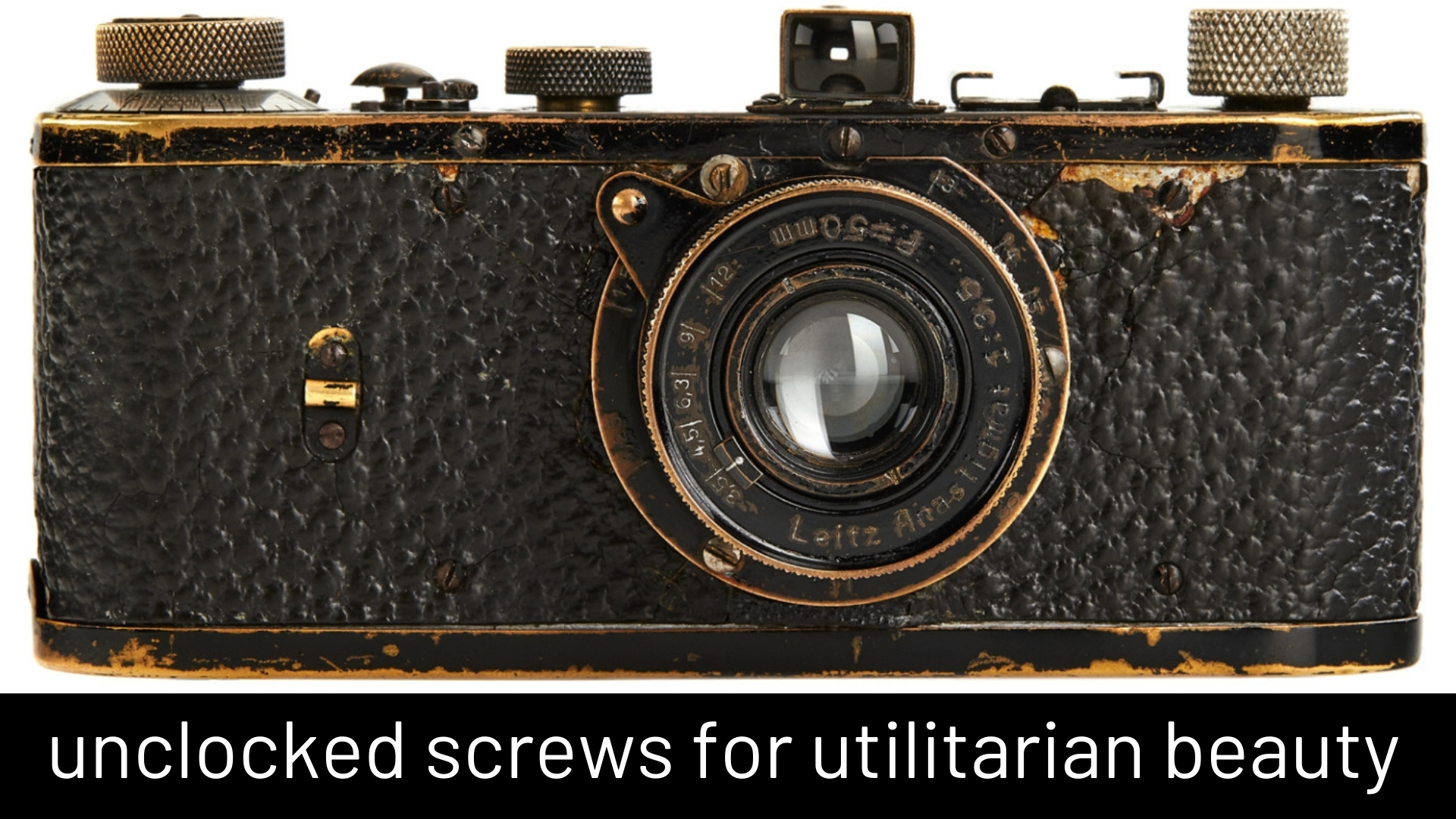

Look at the highest-priced products, and you won't find clocked screws, whether for aesthetic purposes (high-end watches, Rolls-Royce cars, and 0-Series Leica cameras) or critical mechanical safety components (helicopter rotorheads and spacesuits). Clocked screws simply are not applied in the highest quality engineered products.

Clocked screws are a woodworking thing, not a precision metalworking thing. If you're working where precision torque matters, no one clocks screws.

Precision Watches

Look at any $100,000-plus watch screw heads. They're not clocked. (We're not talking about "Royal Oak" faux screws that are purely ornamental.) We're talking about screws that serve a mechanical function.

"You don't see perfectly aligned screw heads in general, pretty much anywhere in watchmaking, and that includes both the humble and the mighty. Even those fanatics of finishing, Greubel Forsey, don't [...] align [...] screw slots — either on the dial side, or in the movement." — Hodinkee Watch Magazine

Even if Seven had the thread-starts for each hole identical, each screw and bolt would also need to be made identically, but screws are not made that way. So, we would have to make the screws from scratch. The cost would be exorbitant but with no functional benefit. Would you really want Seven to charge you for that service? Not even the best watchmakers do it.

“You would have to make sure that the start of the thread on every single screw aligned perfectly with its slot on the screw head. Additionally, the length of the screw thread from the start of its thread to the underside of the screw-head would be critical, and you would have to achieve ridiculously close tolerances.” — Roger Smith in Esquire Magazine

Why clock screws?

Clocking or aligning of slot head screws is sometimes done in woodworking and is usually done for one of three reasons:

- Woodworking aesthetics: Some woodworkers align the screw slots with the wood grain. This would typically result in clocking. It's done for aesthetics, not performance or precision.

- Confirm torque: If the screws are initially clocked, you can tell if one of the screws loosens over time. Fortunately, there are other ways to know if bolts or nuts are loosening. However, in the age of threadlock and spring washers, this is less important. And apparently not important at all if fighter jets don't clock screws.

- Prevent damage or injury: Situations can exist where having the slot turned in a specific way can be more likely to catch on fabric or flesh. Children's furniture is an example. In those cases, it's not really clocking, but rather, overriding the "ideal" torque to prevent snags or injury.

None of these are done in precision metalworking, which has other ways of accomplishing the above three interests.

Historical note: The clock in this image was manufactured for Rolls-Royce by Waltham Watch Company in Waltham, Massachusetts, the next town over from Seven's hometown. This area has always been known for precision manufacturing of watches, bikes, motorcycles, and munitions. And now, Seven Cycles.

Why Slotted Screws?

Sometimes people ask why we use slotted screws (for flat head screwdrivers) rather than Torx or hex head socket screws. A few reasons, including:

- A screwdriver does not offer a lot of torque. For Seven's head tube badge, it's crucial not to over-torque the screw; the threads are very fine, and it's possible to strip them. (Torx are specifically designed for applying maximum torque, so it's the worst choice because the badge is not a high-torque application.)

- Head tube badge threads are small. That means the wrench diameters are very small. A socket drive would be 1/16", and a Torx would be T4 (even smaller than the hex at 0.05" diameter). These are not ideal diameters for those kinds of wrenches; stripping sockets is a thing.

- Easy wrench/driver access: Everyone has a flathead screwdriver. The vast majority of cyclists, even bike mechanics, don't have imperial 1/8" hex keys or T4 Torx wrenches. No bike multi-tool has either of these drives, but almost all include a flathead.

- Socket holes get filled with crud. The smaller the socket, the harder it is to keep the depression clean and free of grit. A slotted head is designed for ease of cleaning, or at least, ease of tool use. (A minor point, but still relevant.)

Screw companies offer different types of screws for various applications. Seven's reasons for using slotted screws provided above come from those companies.

All of the photo examples provided here are slotted (or in one case, Phillips head). Since the world uses slotted screws in these situations, it's difficult to argue that it's a bad choice.

Apprentice Machinist

When our founding engineer, Rob, was young, his mentor, grizzled old master machinist Frank, growled at him one day for clocking screws on a pedal rebuild. Rob, as always, asked "why?" Frank explained:

"Clocking is for ornament. We're precision machinists, not gilders. Never clock screws in metalwork unless it's purely for vanity."

Once Rob recovered from being humbled by his mentor (it took a few years), Rob vowed never to clock another metal-to-metal screw.

Note: Frank was a big ol' teddy bear and just about the friendliest guy we know.

Enjoy More Unclocked Strength And Beauty