Words: Rob Vandermark, Seveneer

The other day, a few of us were discussing the state of gravel bikes and when we first rode what we’d consider a gravel bike. What is a gravel bike, after all, other than a rig you ride on dirt roads and trails? That could be anything. We used to ride our road bikes on trails all the time and still do once in a while. Even Buster Keaton rode a Penny Farthing on singletrack back in 1926 for the film The General.

So, the term “gravel” doesn’t mean much. The definition Seven starts with is “a drop bar bike with at least 38 mm knobby tires and lower gearing than a road bike.” Everything else is open to interpretation.

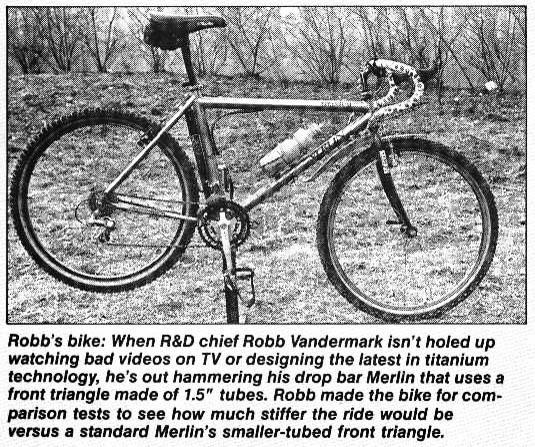

The conversation reminded me of my late ’80s project bike, the Singularity; a drop-bar mountain race bike I designed and built at Merlin Metalworks. This is the only image I can find. It’s an old photocopy of a black-and-white photo from Mountain Bike Action magazine.

Today, this design is called a “monster cross” bike.

Zapata Espinoza, editor of Mountain Bike Action, printed a couple of pages about some of the prototypes and project bikes we had at the Merlin factory. Maybe we’ll share more of those at some point. As far as I can decipher, the photo is from the June 1991 issue of MBA.

I had two missions for this bike project:

- Build a titanium bike stiffer than a Fat City Wicked. At that time, I loved the ride of steel frames. Merlins were super plush, but back then, as a 20-ish-year-old problem child, I didn’t particularly like the Merlin ride. Gwyn Jones (one of three Merlin founders) gave me his blessing to build a super stiff Merlin.

- Build a singularity bike. At least, that’s what I called it. The plan was to have one bike that I’d race road, mountain, and downhill on. That’s a whole other story for another time.

I accomplished both missions with the Singularity. It was way too stiff (particularly because it was the days before front suspension), but I found it race-worthy in the woods and in criteriums. This bike started me on the path of size-specific tubesets and the realization that tubing specification really matters quite a lot.

The bike was a prototype on a number of fronts, not just because of the drop bars. Here are the elements I remember that were unique or firsts back in the late ’80s:

- 1.5″ down tube and top tube: This made the front end stiffer than the standard Merlins by about 60%. At the time, Merlins had 1.25″ front triangles. Interestingly, the Fat City Wicked of that time had front-end stiffness similar to that of the original Merlins. My Merlin Singularity’s front end was about 40% stiffer than a Wicked.

- 1.5″ seat tube: This was wild at the time. Steel frames typically had 1.125″ seat tubes, and a few aluminum bikes had “massive” 1.25″ seat tubes. Because I wanted a super-stiff drivetrain, I thought I needed the seat tube to be ridiculously oversized.

- A custom-modified front derailleur: The 1.5″ seat tube meant that a standard derailleur clamp wouldn’t fit. Even today, there’s no 1.5″ front derailleur with a 38.1 mm clamp. I machined some parts and rivet-nutted the derailleur directly to the frame. Then, I had to modify the derailleur to get more inboard swing to the cage. It worked well, but I could see the tube warp during shifting under load.

- Custom seat post sleeve: The seat tube, being so much larger than a standard diameter, required a special seat tube insert. I machined it from titanium and welded it in a series of overlapping sleeves that looked a bit like Swiss cheese with speed holes everywhere.

- Hot swap bar system: I had a quick connect hot swap setup for the bars. I could remove the entire bar and stem assembly as one unit and switch between drops and flat bars. I’m sure someone had done this before, but it was the first time I’d seen it.

- 5 cm stem: The stem was progressive even by today’s standards. In the photo, and in my memory, it looks like about a 5 cm stem. It was an old quill stem from a Columbia(?) cruiser. Chipped chrome plating and rusting in places. It had a socket head thru-bolt to hold the wedge in place and a socket bolt for the bar, too. I went with this stem because, with the hot swap system, the stem’s short reach worked better with the drop bars hood grip reach compared to the mountain bar grip reach. I had been building titanium stems by this point, but I was in a hurry, so I went with what I had in my parts box.

- Shoulder strap pad: In those days, mountain bike courses were a bit different than today. There was almost always some hike-a-bike. I used to love those sections. The shoulder strap made shouldering comfortable and a lot easier to run with. I had the strap rivet-nutted to the frame.

- Double wheel system: 26 x 2.25″ mountain bike wheels and 26″ x 26 mm road race wheels.

- I wasn’t aware of anyone doing this back then. While Specialized offered a 26″ x 26 mm road tire, I hadn’t seen anyone use it for a mountain and road bike in one.

- I was able to use 700c Mavic road rims cut down and rerolled to 26″ size. Keith Bontrager was making them at the time. Super light and super narrow. Can’t have everything. I loved them. The rim width had to be identical for both wheels so that the cantilever brakes would work properly. That meant very narrow mountain bike rims.

I designed, machined, and welded this frame.

Mountain bike performance results: I think I raced and trained offroad on the drop bar setup for about a year and a half. Once I had the bike in the drop bar configuration, I rarely swapped it to the mountain bar setup. I loved drops.

Road bike performance results: I raced many a local training criterium on this bike.

The bike’s weak point was the drop bar brakes. The lever arms for drop bars were different from mountain bike levers, so it was difficult to get enough braking power from the cantilever setup. Also, the brake levers themselves were too small for my hands and, therefore, difficult to hang onto during rocky descents. Otherwise, it was a good setup that got me through many rides.

I don’t recall what happened to the Singularity frameset. I was never much of a keeper. Of the hundred-plus prototypes and project bikes I’ve built over the years, I kept only one.

Hat tip to John Tomac, one of my cycling heroes. He used to race drop-bar mountain bikes back in 1990. I think I might have first seen him race that way in 1989, but I can’t remember. The internet says 1990.

Photo caption explained: Zap had this weird thing where he’d add a second last letter to our first names. Don’t ask me why. Zap stayed at Merlin for a few days. When not riding and talking shop, a group of us watched some bad movies, as he mentions in the photo’s caption. I don’t recall what we watched, but I’d wager there was a Godzilla movie on the docket and probably something starring Burt Reynolds. I recall that Zap was not impressed with the humor. I forgave him because he was, and is, an incredible documenter of the times. No one did more for mountain biking in the early days than Zap and Mountain Bike Action. Here’s to Zap for documenting so much over the past 35-plus years in Mountain Bike Action, Road Bike Action, and other media.

+++

Time tracking: Frame build date circa mid-1988. I estimate that date range in part because Zap visited Merlin in the winter of 1989-1990. (I remember riding with him in the freezing cold. Fine riding weather for us Bostonians, but not great for a guy living in LA.) The bike was pretty beat by the time he took this photo. I must have had about a season of riding on it already.