Carbon Frame Stiffness Declines Over Time

This information is summarized from Seven's Carbon Frame Downfall white paper. Additionally, all source material and footnotes can be found in that paper.

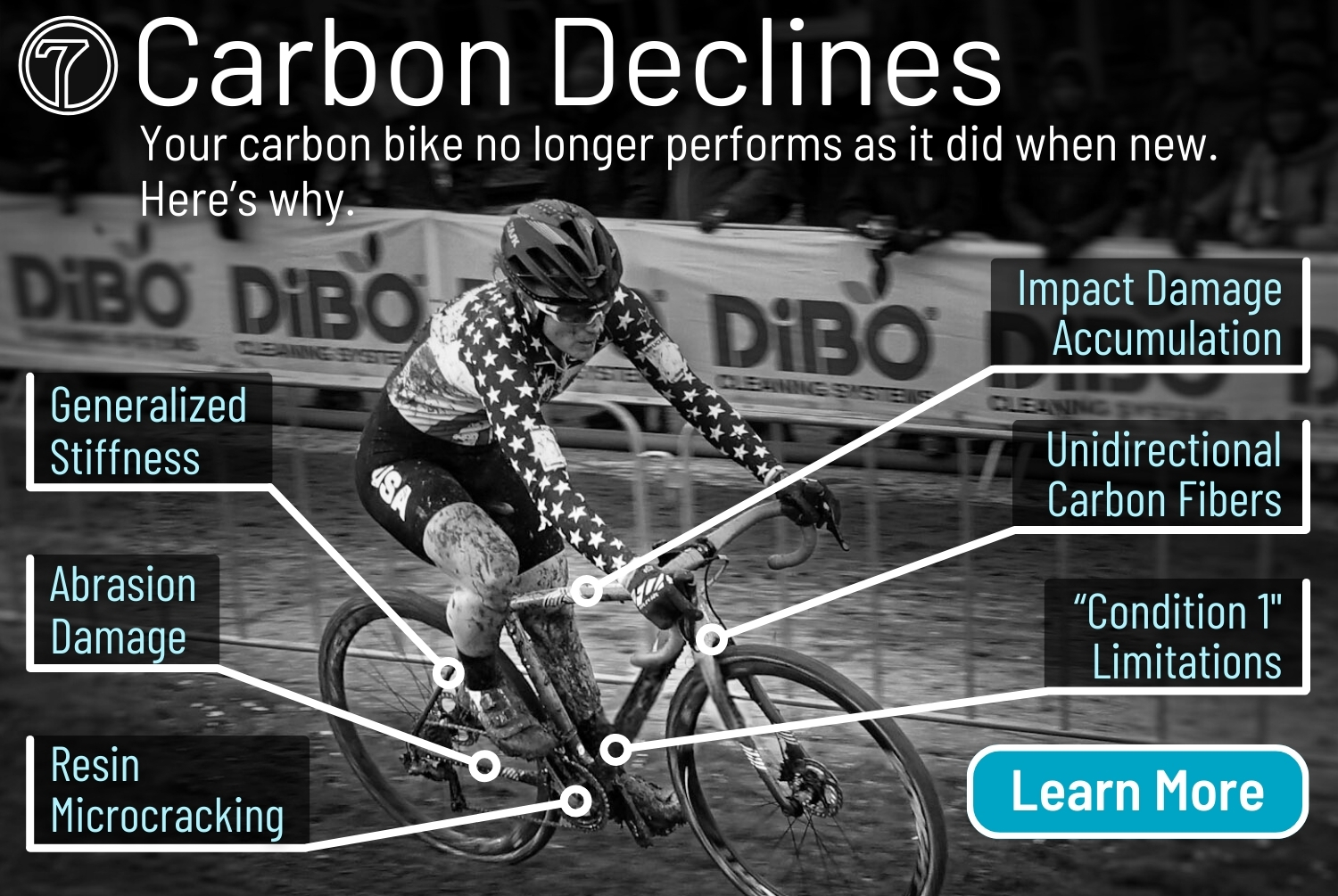

Here are some of the causes of stiffness decline in carbon frames, in no particular order.

All statements and data presented on this page are verifiable through the source materials provided in the associated links below.

Stiffness Loss Happens Without Exception

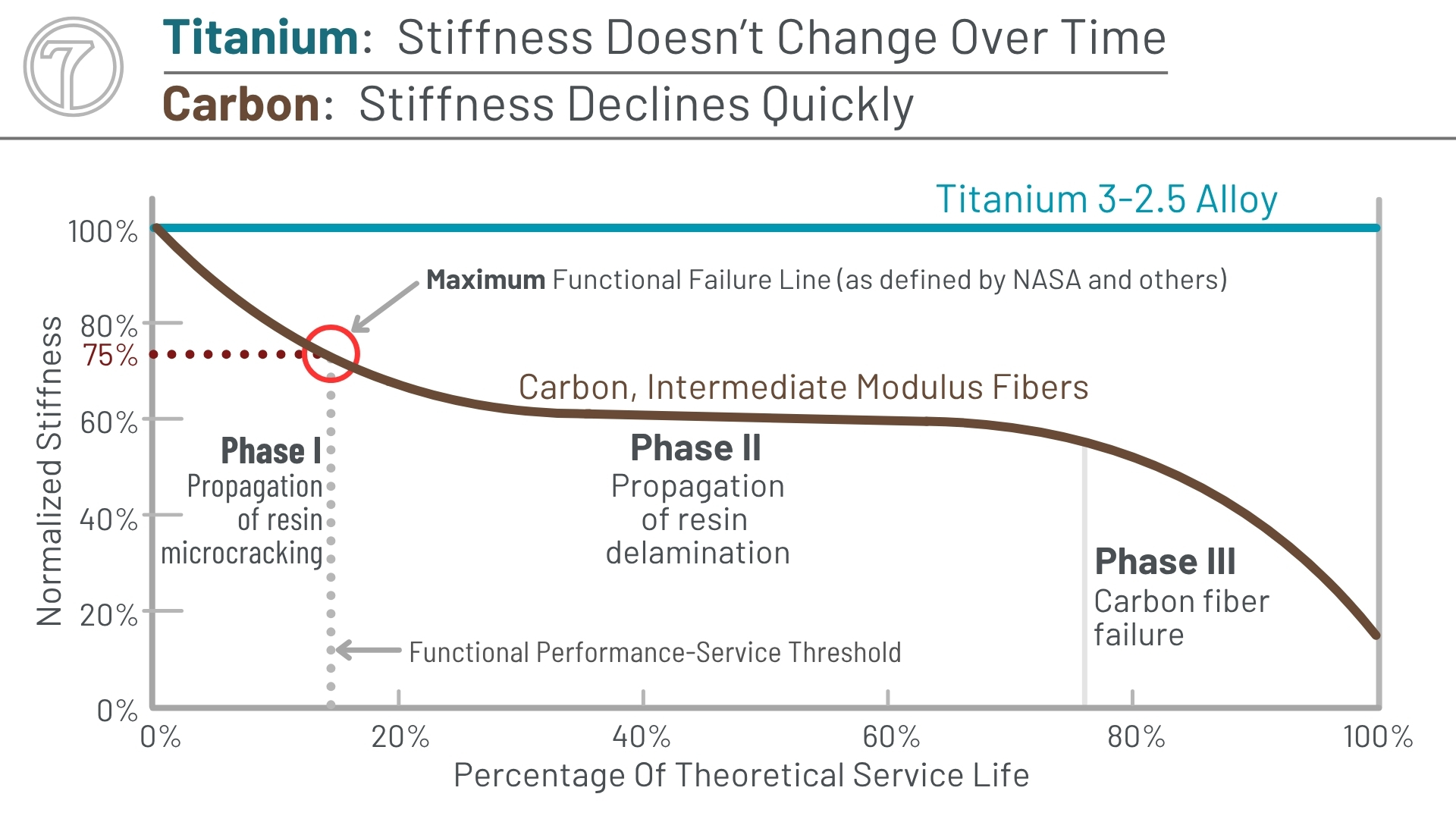

Most riders don't believe carbon gets less stiff with use over time. That's understandable because the change occurs slowly; the rider's body adapts to the ever more flexible ride. So, here we start with evidence that it does happen.

If the industry's testing standards acknowledge and account for inevitable stiffness loss, then it's reasonable to assume that, in fact, carbon frames and forks get softer over time. The ISO 4210 standards say that a 20% stiffness decline in a carbon fork means it did not pass the test. It is considered a failed fork and not safe to ride:

ISO 4210 "Conclude the test if the running displacement (peak-to-peak value) at the point where the test forces are applied increases by more than 20 % for rigid forks or more than 40 % for suspension forks from the initial values (see ISO 4210-3:2023, 4.6)." ISO 4210 standards. Must be purchased to read the complete standards.

The DIN 14781 test standard for frame fatigue reads the same as forks — a 20% decline in stiffness means the frame failed the test:

"For carbon-fibre frames, the peak deflections during the test [...] shall not increase by more than 20% of the initial values." DIN 14781 standards. Must be purchased to read the complete standards.The DIN standard was superseded by the ISO 4210 standard in 2015. Regardless, the DIN is relevant because it shows a shift in thinking about frame durability and safety. And it doesn't make much sense. No one states the issue with clarity but AI says that fork fatigue testing uses 20% stiffness loss as failure because a failed fork is extremely dangerous. Frames have no lower threshold for stiffness because frame failure isn't dangerous. This doesn't make any sense. Some argue that modern carbon frames are trying to have compliance and that's why no lower stiffness threshold exists. The problem with this argument is that the 4210-6-4.3 frame fatigue test uses pedalling force. Most riders want the bottom bracket area and drivetrain overall to be as stiff as possible, not as compliant as possible. The idea that flex is a benefit in this test makes no sense.

Read more about this 20% stiffness problem in Seven's frame and fork comparison.

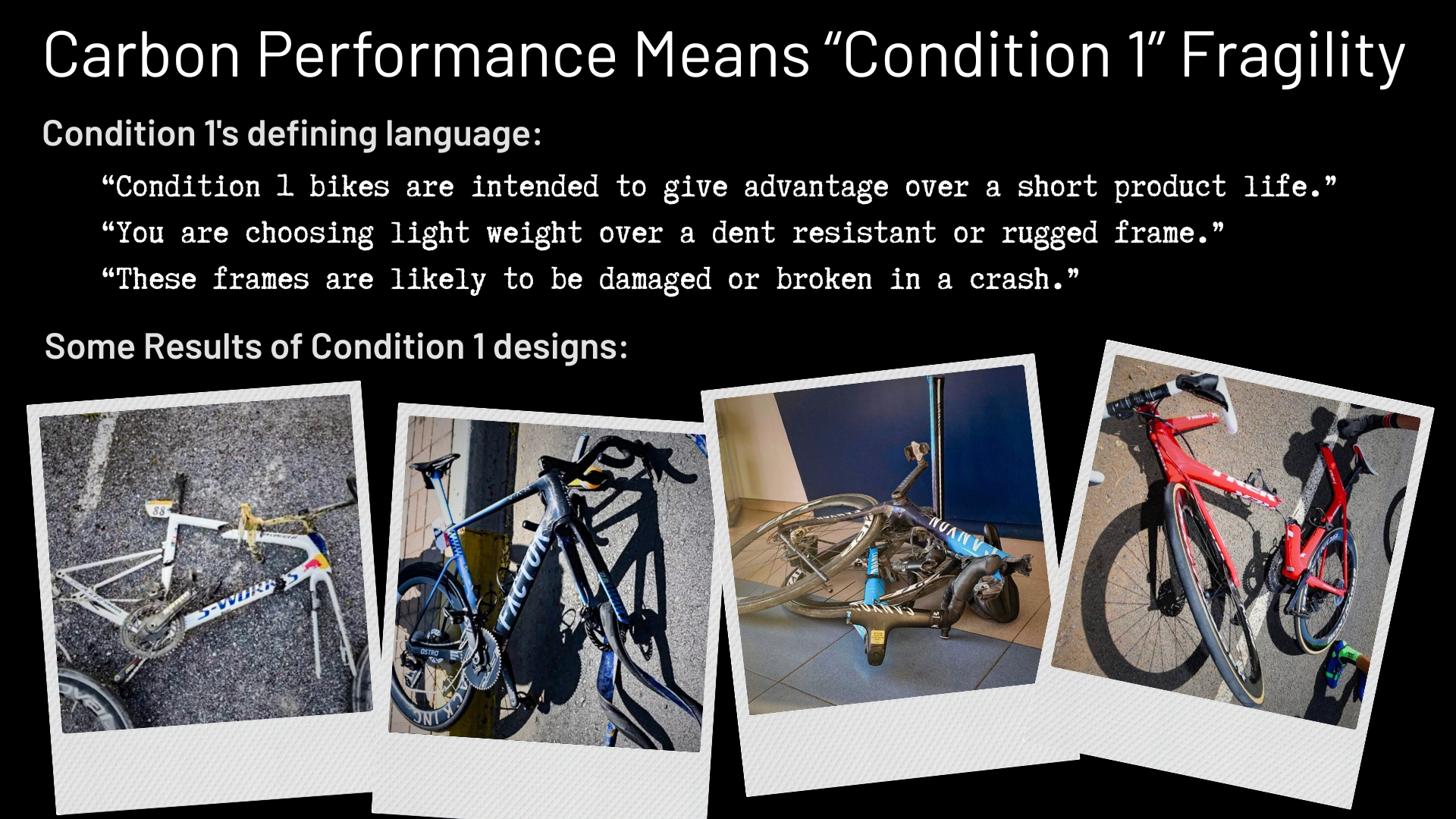

"Condition 1" Limitations

If you've purchased a performance carbon road bike from a large brand in the past few years, the frame is probably designed within “Condition 1” riding constraints, along with a number of warranty implications.

Condition 1 is a term for very fragile carbon frames. Almost all high performance carbon road frames fall under Condition 1.

Text from the owner's manuals of many prestigious carbon bike suppliers describes the durability problems well. Here is verbatim text from those manuals:

“You are choosing light weight over a dent resistant or rugged frame.”

“Condition 1 bikes are intended to give advantage over a short product life.”

“These frames are likely to be damaged or broken in a crash.”

Read more about Condition 1 carbon issues.

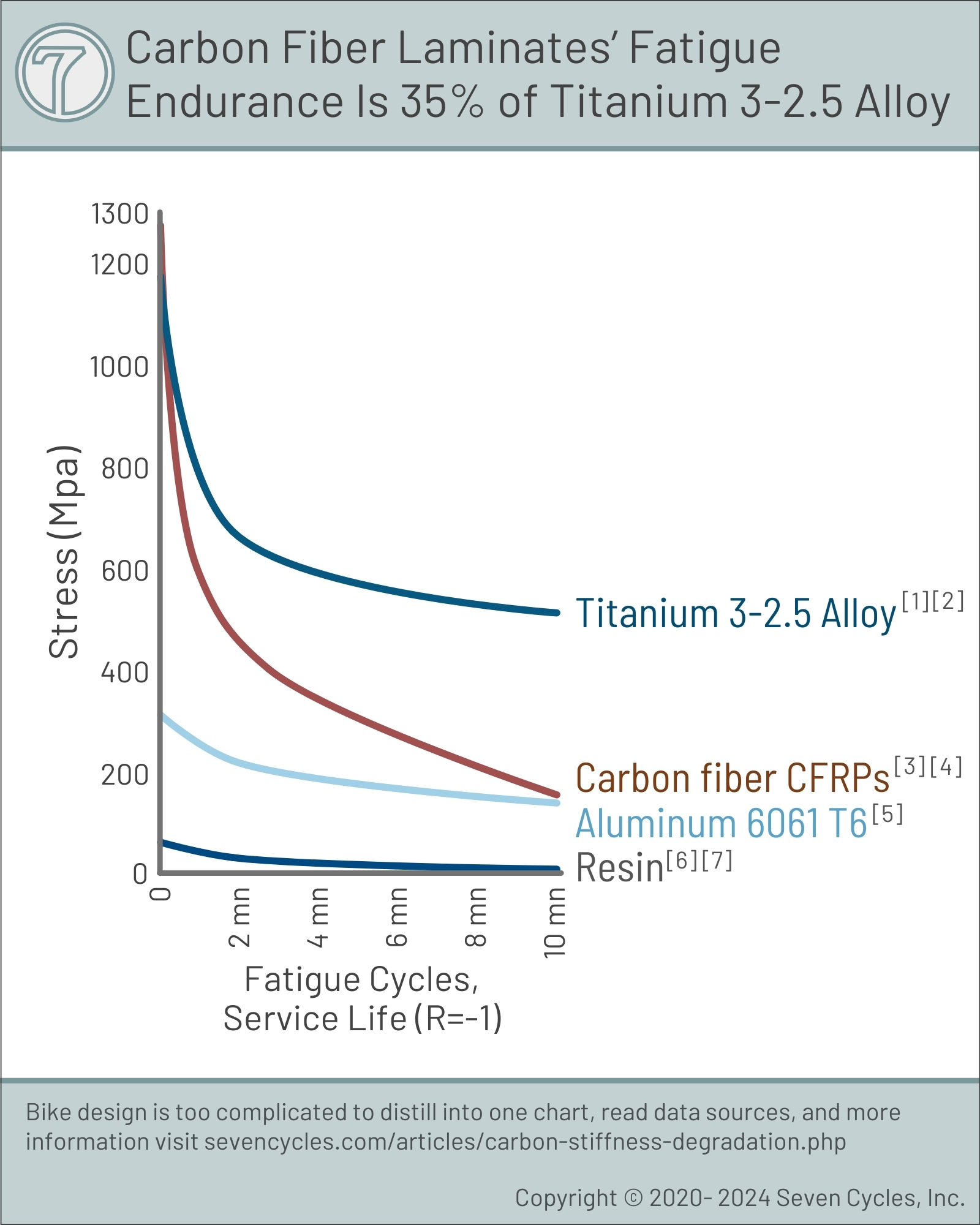

Resin Microcracking

Carbon laminate stiffness degrades immediately upon the introduction of cyclic load — pedaling a bike, for example. Soon after, the structure begins its inevitable, slow slide to ever-increasing flexiness until the frame fails or is replaced.

The cause of resin cracking is its dreadfully low fatigue strength. Resin's fatigue strength is only 10% of that of aluminum 6061; in practice, that's not functional strength. The resin begins its failure journey on the first ride.

Read more about resin and microcracking problems in Seven's carbon white paper.

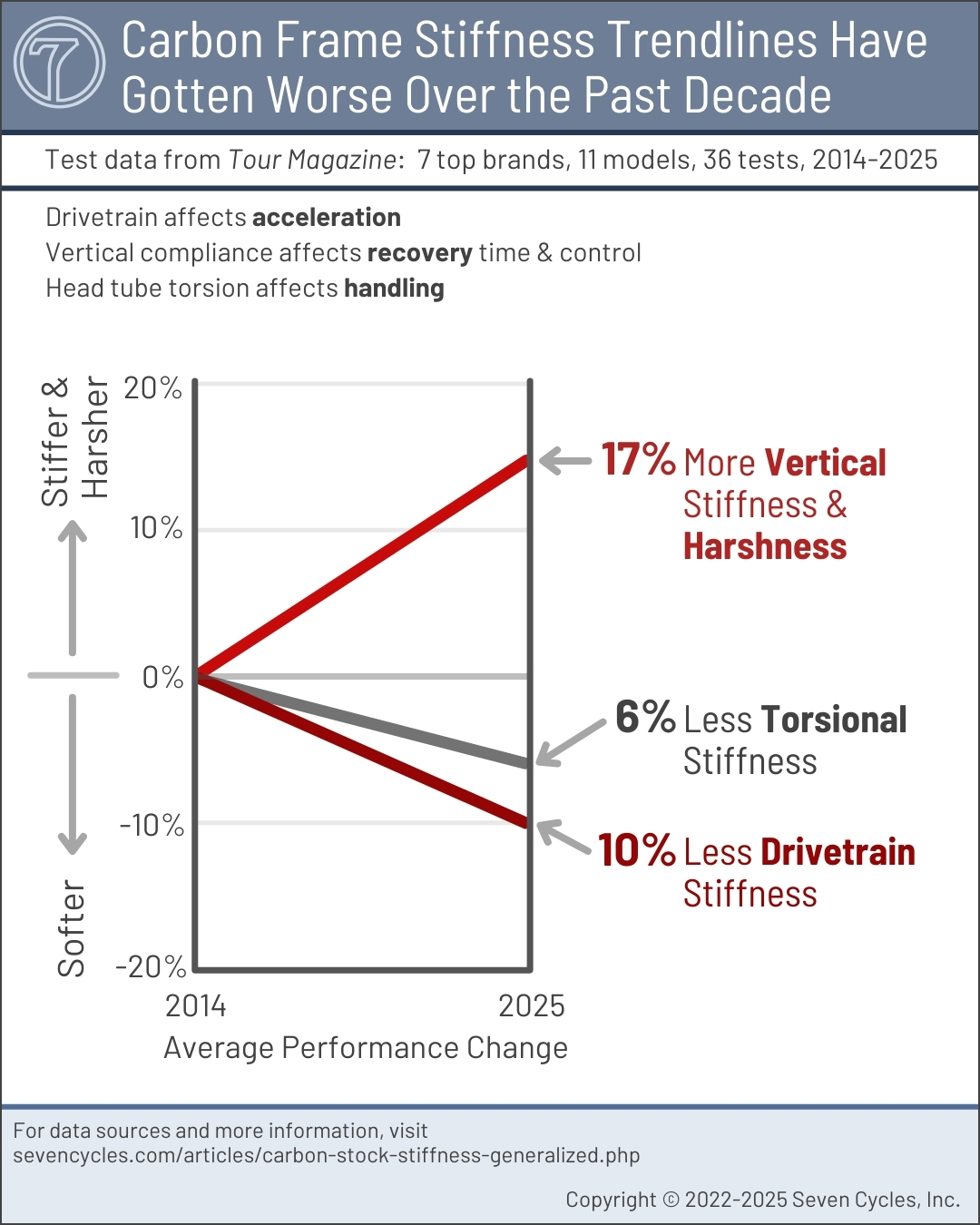

Generalized Stiffness

Generalized stiffness is Seven's term for one of the primary and intractable issues with carbon frames. As illustrated in the adjacent figure, carbon frames must distribute stiffness suboptimally. The frame requires too much vertical stiffness (to delay failure) and, because frames need to be so light these days, there's not enough drivetrain stiffness.

The result is a frame that is generally stiff, but not stiff enough laterally and too stiff vertically, the worst of all worlds.

Read more about carbon's stiffness conundrum in Seven's carbon white paper.

Abrasion Damage

Mud, sand, grit, debris, frame bags and straps, chain drop, and even shoe heels all abrade carbon fiber. Carbon can wear to failure rather unexpectedly and quickly.

The Abraded Stay photo shows layers of carbon worn away by a muddy tire. The damage occurred in a single day's ride of Unbound (a 200-mile gravel race). The bike should not be ridden without repair. Writing for Cycling Weekly, the author and owner of this bike, Anne-Marije Rook, wrote of the damage done:

"On the chainstays, seat stays and seat tube, the grime and grit had worn through [...] most of the carbon."

Read more about carbon's abrasion problems in Seven's carbon white paper.

Impact Damage Accumulation

Carbon fabric, filled with resin and formed into thin-wall tubing, is not damage-tolerant compared to metal tubing. Crashing the bike, dropping the chain, dropping a wrench onto the frame, or the bike falling over. Any are likely to end a carbon frame's life.

Read more about carbon's impact problems in Seven's carbon white paper.

Unidirectional Carbon Fibers

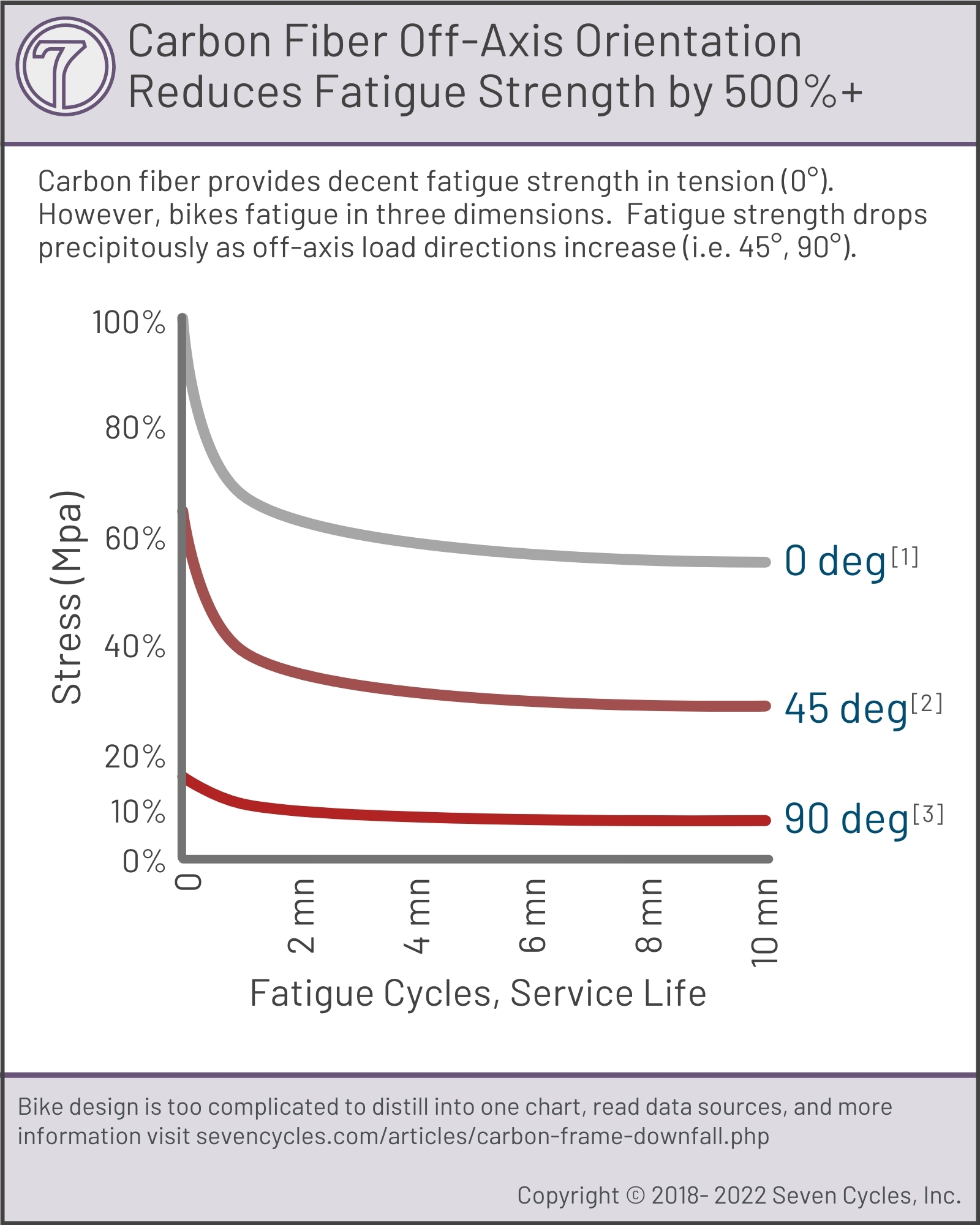

The orientation of bike frame fatigue is not monolithic. It occurs in all planes of the frame. As illustrated in the Carbon Off-Axis Fatigue Drop figure, carbon only has reasonable fatigue strength in its tensile direction (0°), not in any other direction (bending, torsion, or compression). Therefore, carbon is prone to failure in off-axis load situations (i.e. 45°, 90° stress),like those found in bike frames.

Titanium is monolithic in fatigue endurance (equal durability in all axes). Carbon's unidirectional fatigue strength requires 4 to 6 layers to begin to replicate titanium's monolithic properties. This means a heavier carbon frame that's still not optimized for three-dimensional stresses (lateral, tensile, torsional, compressive, vertical).

Read more about carbon's unidirectional fiber problems in Seven's carbon white paper.

Footnotes