By Steve Medcroft

The first Seven I ever saw up close was Mary McConneloug’s Tsumani cyclocross bike. She rode it during the 2004 U.S. Gran Prix of Cyclocross series. We wrote a pro bike report on it. Her partner and teammate, Mike Broderick, said that Mary had been riding the same frame for three years and that fact stuck in my head. Three years. Most riders are issued new bikes every year. Most bikes are changed and modified enough each season that the manufacturers have to upgrade their sponsored riders.

But three years before our article, Seven Cycles fit Mary for her Tsunami and she hasn’t needed to replace it since (and was giving no hint that she intended to replace it any time soon). It left me with the impression of a Seven as a lifetime purchase, a frame that would be with its owner forever.

I ran into Mary and Mike at Interbike this year. Mike and I were eyeballing Seven’s IMX hardtail mountain bike; which features titanium lugs and carbon tubing. We were talking about the way the bike rode and he was explaining how Seven tunes the bike for each buyer through a customization process that factors in something like one hundred data points. From how you like the comfort of the bike vertically to how stiff you want the torsional drivetrain, you can have a Seven built to ride and feel exactly like you want it (or exactly the way that will emphasis your riding and racing strengths and minimize your weaknesses).

But Seven isn’t a typical custom bike builder (a small shop designed around a single master frame builder); it’s an eight-year-old, 35-employee, Boston-based bike manufacturer. How do they mass-produce highly customised bicycles? I couldn’t pass up the chance to swing into the Seven factory after covering the USGP stops in Gloucester the weekend of Halloween.

First impressions

Seven got its start in January, 1997 when Rob Vandermark, head designer for Merlin Bicycles, struck out with a small group of colleagues to occupy a 1,000 square-foot corner of someone else’s machine shop 30 miles north of Boston. “The guy who owned the shop was extremely generous to us,” said Vandermark when I visited the company. “He was excited to see us get off the ground. We grew to twelve people quickly with everyone doing everything from welding and machining to sales and R&D in that tiny space.”

Vandermark, an engineer by practice, had a vision for an industrial process that could bring hand-built custom bicycles to an audience as large as a mid-sized mass-producer. He says he felt that the larger companies were too inflexible to truly process customization through their company’s systems and most custom builders were limited in size due to their single-handed approach to customization.

Seven executed Vandermark’s process in that small space until they moved to a 12,000-square foot facility in the lower level of an industrial park in Watertown, MA, about six miles from Boston Harbour as the crow flies. At the company’s front door, there is no fanfare, no neon-lit 20-foot-high Seven logo. The door is, in fact, almost hidden from view in a cul-de-sac at what looks like the rear of the building. I actually walked up to the door and backed away, convinced it was a private entrance or a loading dock and circled the whole building looking for a front entrance before coming back to the cul-de-sac.

I sat with Director of Marketing, Jennifer Miller, in Seven’s showroom, a cavernous, brick-walled corner of the space complete with racks of completely built Sevens along two walls. The display was a good example of Seven’s line: bikes designed for all different types of riders (The Elium competition road bike, The Alaris Race crit bike, the Axiom Steel for traditionalists, Sola for cross-country racing or Duo for all-mountain riding).

One thing that stuck out about that selection of bikes was the variety of frame materials. I always thought of Seven as a ti shop. “From day one, we worked with materials other than titanium,” Miller said. “The first bike we ever made as a company was steel. We were also working with carbon fibre from day one and introduced the Odonata – the first bike to strategically employ both carbon fiber and titanium tubes – in our first year. The design inspired a revolution; within a year, everyone was doing metal bikes with carbon seat stays, etc.”

Miller’s point is that to Seven, the frame material isn’t the focus of bike (most frame materials can be manipulated to produce almost any desired effect), it is the ultimate one-bike-at-a-time tuneability that can be achieved with almost any frame material that matters most.

A Fit for a King

To learn about the customisation and fit process, Miller introduced me to Zac Daab, Seven’s Senior Fit Specialist. Seven’s bike-build process starts when the retailer fills out a comprehensive customer questionnaire to gather everything they need to know about the rider’s desired fit and comfort, handling and performance, tubing and materials preferences, features and options and any accommodations the bike needs to be ready for the rider’s future.

“The questionnaire contains the hundred-plus data points we use to come up with the final build,” Daab said, using a marked-up (the document is continuously refined) copy of the Custom Kit to make his point. The goal is to gather enough data to build a custom frame without ever seeing the rider, so beyond the questions that can be answered by measuring a rider’s legs, arms, wingspan, inseam, etc, Seven asks about a rider’s weight, their previous bike, the components they plan to run, what kind of riding or racing they do. “We want to know if they are using riser bars,” Daab says, “how they want their cable routed, do they want pump pegs, the color of their decals.” Every answer matters. “Fork choice is important, for example; it can help us change the geometry of the front end of the bike.”

Daab says that Seven asks questions customers aren’t used to answering when they buy a mass-produced bike. “When you buy a bike off the floor, for example, it doesn’t matter if you’re doing centuries, crits or full-on time trials every weekend; the handling for that bike has been selected already. By handling; we mean things that control handling; the head tube angle, the bottom bracket drop, the chainstay length – they are already figured out and it doesn’t matter who you are. With a Seven, what we’re working on through the Custom Kit is how to build the perfect bike for that single rider.” That data gathered in the Custom Kit is balanced into a frame design that sets the rider in a neutral position with as much component adjustability as possible.

To prevent ambiguity, a Seven fit specialist calls the buyer directly before a final design is committed to production; a practice Daab says Seven remains committed to event though it has become a much larger task than when Seven was small. “Sometimes we’re resolving inconsistencies – if you said the reach of your current bike felt way too long but we’re looking at your body data (arm length, body length, top tube dimensions) and it doesn’t seem to check out, we want to talk about it with you to make sure we build exactly the right thing. The call is about tuning the build a little bit tighter.

Sweeping the Factory Floor

At about day eleven in the four to seven-week process, the customer signs off on the build then a build sheet, detailing the frame’s design, is sent to the floor. I left Daab, and Miller led me through a double door to view the frame production area. With concrete floors and work zones crammed with stock, machinery and welding equipment, the Seven factory floor is a genuine production facility; a dirty, grungy, make-something-with-your-hands kind of place.

At first pass, it looked chaotic, but although it was a little cramped (Seven has signed a lease on an adjacent space and will double the production floor in early 2006), there seemed to be purpose in the placement of ever person, every tube, every lathe and drill press.

Seven frames begin life in the frame stock bins. Stock tubes are cut, shaped, bent and butted into what is essentially a bike in a box; literally, a shallow, cardboard box filled with a jigsaw puzzle of metal tubes that will be tack-welded together at the next work station. Once the tubes are tacked into geometric position, the assembly is passed to the welders.

“Tim Delaney is a career-professional bike builder,” Miller said as we watched the lanky Delaney work the head of his Tig welder around the contours of a bottom bracket. “He’s been welding his entire life. Most of our other welders have been trained here. They may receive up to six months of training before they even tack a frame.”

A braided hose hung from a coupling attached to the bike’s head tube. “The frame has to be completely sealed,” Miller said. “It’s filled with Argon (an inert gas) to purge Oxygen and other environmental elements that could compromise the weld’s intergrity if present when the titanium is in a molten state during welding.”

When the welders (of which there are several besides Delaney) finish the frame, any carbon elements are screwed and glued in place, the frame then receives its final pieces and parts then moves on to the finishing stations where they’re buffed and prepped for painting and decals.

Before and after finishing, the frames hang on a rack for Quality Assurance to make sure there’s no reason to send them back to the floor before the final product is shipped.

Knowing which way the rudder is pointed

The fact that the core of the thirty-five employees at Seven are cyclists is evident; many wore long-sleeve wool jerseys and a half-dozen people arrived to work on bikes during my time there. But just as many employees learn their passion for cycling by working at the company. “We have a really good employee purchase programme,” Vandermark said, “We offer a very, very low price. And to the extent our employees can do any work on their bike off the clock, that’s totally taken off the top.”

So at Seven, there are a lot of people paying a few hundred dollars for very expensive bikes. “And there’s a lot of bartering going on,” he added. “A welder who can’t machine will go to a machinist who can’t weld and they’ll trade work on each other’s bikes. We have employees that have built five, six, seven bikes over time. Which is important to us; it helps to have that appreciation when you’re stressing and fussing over details.”

I asked Miller where she thought Seven would be in five years and she grinned and leaned forward in her chair. “We want to grow but we measure growth in different ways. Clearly, sales is one reason to grow and one way to measure growth, but growth also represents the opportunity to do the kind of product development we want to do, to reach that size where we can support things like health insurance and 401k’s and profit sharing. A certain amount of growth is necessary to be able to create the kind of company we want to be.”

What Miller is hinting at is something every small to mid-sized company struggles with; how do you create opportunities for smart and talented people to grow within your organisation when there are only so many ‘big’ jobs to do? “We hire a lot of creative people (an unusual number of art students, Miller told me earlier). It’s important to us that we give them a real career path; a way to start at the entry-level and develop a real career for themselves.”

The company is also dealing with the transition beyond Rob Vandermark’s ability to manage every aspect of Seven’s operation. “In the early years,” Miller says, “we had to manage growth in a different way. We couldn’t keep up with orders. As we mature, we know we have to be more sophisticated with how we chase growth. We need to bring in other perspective and we need to spread the burden of growth. I see that as our big challenge but I feel like that’s an issue most companies our size have to deal with so I’m sure we can work through it.”

There’s also the challenge to Vandermark’s customization process. Can it stay intact if Seven becomes, say, three times its current size? “It doesn’t scare me,” Miller says. “When people say ‘how can you continue to profit with a single-piece flow like that’ I just think back to when we first started. Our labor hours per bike are so much lower now than they were then. I’m confident we’ll continue to get smarter.”

Seven Partners on the Racecourse

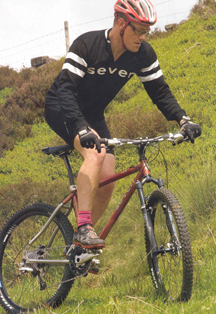

It is not uncommon for a bicycle manufacturer to promote its product by sponsoring racers or a racing team. Seven Cycles is not a big-budget, mass-market brand so it has passed on the cost and logistics that come with the opportunity to outfit a 13-member road team and instead works closely with racing and life partners Mike Broderick and Mary McConneloug.

“We can be seen as a road manufacturer so sponsoring a mountain-bike team is odd,” Seven’s Jennifer Miller said during my visit to the company’s Boston factory. “But most of us here at the company, the founding team, were seriously into mountain biking – we all raced and we loved it – so we’re almost living vicariously through Mike and Mary.”

Don’t get Miller wrong; sponsoring McConneloug and Broderick isn’t a corporate whimsy. “Our relationship goes back almost five seasons now. I was racing mountain bikes at the time and Mary won a race that I and another member of our team was in. When Mary and Mike approached us after that about sponsorship, they presented us with a serious and professional agenda.”

The couple seemed to align philosophically with Seven’s founding team as well; they showed a focus on the environmental issues surrounding mountain biking just as Seven has implemented environment-friendly policies throughout the company. “That part of it mattered in a lot of ways,” Miller says. “And since Mary and Mike have increasingly done better and better year after year, we’ve been happy to keep working with them.”

Could Mary and Mike’s success make them more attractive to a bigger-budget team and pull them away from Seven? “Every year, we wonder whether we’ll be able to maintain this relationship,” Miller says. “And I wouldn’t blame them one bit if she was looking for something big. But part of their values are that they want the freedom to race what they want to race and they feel strongly about the companies they work with. Since we feel like we’ve formed a relationship with Mary and Mike and that our sponsorship is not purely a commercial enterprise, there’s no reason why we won’t continue to work together.”

Rob Vandermark’s Resume

1987

— Vandermark is involved in designing and building frames for Olympic medal winners, world champions and Tour de France winners including Lance Armstrong’s Subaru-Montgomery team.

1990 — Designs custom frames for Greg LeMond and his Tour de France winning Z-Team.

1991 — Began two-year study of wheelchair ergonomics and develops revolutionary wheel chair designs. Applies this knowledge of ergonomics to bicycle fit and design.

1992 — Introduces the industry’s first size-specific tube sets.

1993 — Introduces racing wheelchair for Bob Hall (the first wheelchair athlete to complete the Boston Marathon and who went on to form Hall’s wheels, a racing wheelchair supplier). Scientific Frontiers television program calls the chair “A design revolution.”

1994 — Introduces innovative light, mobile, and with a low center of gravity everyday wheelchair.

1997 — Leaves Merlin and launches Seven Cycles using the Custom Kit and Client Interview processes which allows Seven to produce highly customized bicycles in a mass-production scalable system.

2004 — Seven Cycles fits and builds 10,000th bicycle frame.